Date Posted: 04.03.2024

With 3,300 miles of coastline exposed to sea level rise and coastal flooding, Washington state is ramping up its work on resilience planning and design. The San Francisco Bay Area and Vancouver, BC also have ongoing efforts to advance regional shoreline adaptation and collaboration.

Initiatives in all three places illustrate how coastal adaptation can shift the needle for the better, bringing immediate and direct benefits for communities affected by coastal flooding and sea level rise — often communities of color or low-income rural communities that have been historically disinvested. To achieve these far-reaching benefits, adaptation can build from Indigenous values, advocacy, and science, increase the health and scale of shoreline ecosystems, connect people safely to the shoreline, and address other community priorities through equitable investments.

Though they range widely in focus and scale, examples in each place embed equity and justice considerations, and connect long-range coastal-adaptation visions to current community priorities. These visions are setting the stage for regulatory shifts, cross-jurisdictional collaboration and alignment in built projects.

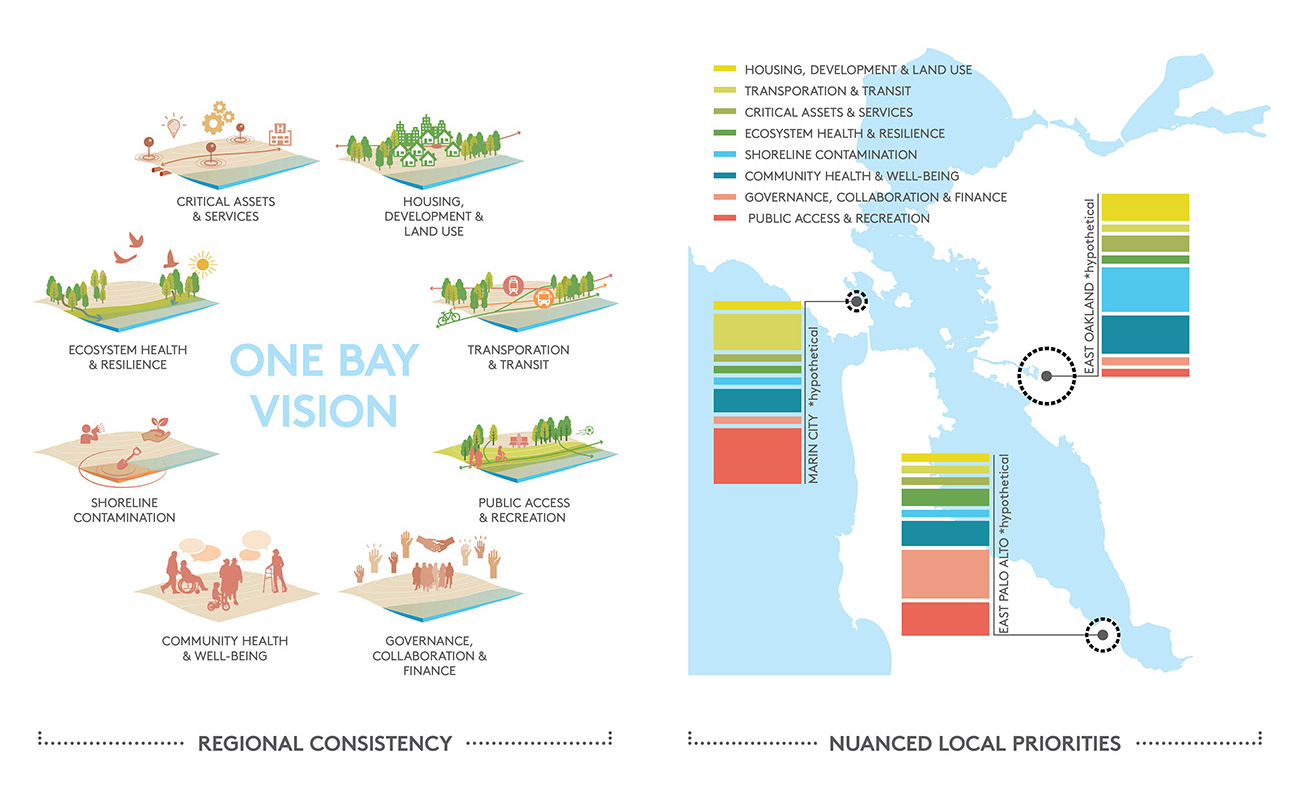

A hypothetical Illustration of how planning guidance can be flexibly calibrated to local conditions and priorities in support of a regionally consistent One Bay Vision.

Bay Area: planning for regional alignment and place-based nuance

The San Francisco Bay Area is currently developing its Regional Shoreline Adaptation Plan (RSAP), to guide “the creation of coordinated, locally planned sea level rise adaptation actions that work together to meet regional goals.”

Mithun is working alongside the Bay Conservation and Development Commission to develop planning guidelines that will direct subregional shoreline adaptation plans across the nine-county Bay Area. The “One Bay Vision” and RSAP guidelines will align adaptation plans and projects through a common set of baseline assumptions and targets, while recognizing that capacities and conditions range widely across the Bay.

To embed equity and justice considerations into a project of this scale, recurring equity assessments with an equity subcommittee allow for continuous recalibration and questioning of assumptions, language and process. To facilitate regulatory change and coordinated implementation, the team is working to connect guidelines with specific updates to existing plans.

With a draft of the guidelines developed, the team will be holding place-based workshops throughout the Bay with community-based organizations to understand how guidelines may apply differently based on unique conditions and community priorities, and to inform refinement of the guidance for ease of use, flexibility and effectiveness.

A vision for the future of south False Creek increases connection to the water, centers Host Nations and restores the historic shoreline in Vancouver, BC.

Vancouver: Committing to reconciliation along a restored shoreline

The Sea2City Design Challenge, completed in 2022, sought an achievable but compelling vision to guide long-term sea level rise adaptation along False Creek in downtown Vancouver, B.C. Extending beyond a focus on flooding, the challenge was rooted in an explicit commitment to truth and reconciliation with the xwməθkwəy̓əm (Musqueam Indian Band), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish Nation), sə̓lílwətaʔɬ (Tsleil-Waututh Nation), and urban Indigenous communities in the region.

Public events communicated the flood risks along False Creek and offered culturally based events to discuss which values and priorities should guide the design challenge. The city distilled this feedback into seven categories of community values, and worked with Host Nation representatives to co-author an Indigenous Knowledge Value Guide. These values were a guide for the work and were also used as evaluation criteria to confirm that design proposals responded to the established priorities.

The city prompted both teams — the Mithun + ONE Architecture team for South False Creek, and the PWL + MVRDV team for North False Creek — to center decolonization in their design processes, exploring ways to move toward shared land management and financial benefits for Host Nations. Each team worked closely with a Cultural Advisor and a Knowledge Keeper, and heard from Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh speakers in multiple decolonization and Indigenous perspectives workshops.

This was an impactful process, and led to visions that reframed traditional adaptation planning strategies into language and concepts that better reflected a repaired relationship between people and water; for example, using “acknowledge / host / restore” rather than the traditional “resist / accommodate / avoid” terminology to describe adaptation scenarios.

With this grounding in reconciliation, the Mithun + ONE team envisioned a decolonized shoreline as one that is “unbuilt” and co-managed — removing historic fill, shifting development upland where it is naturally protected from sea level rise, and introducing nature-based strategies that bring back healthier creeks and tidal ecosystems to help clean contamination and reconnect people with the abundance of marine life and daily tidal changes.

Realizing this vision while respecting the lives and livelihoods of those living and working along the shoreline requires an adaptation pathways approach, considering when buildings along the shoreline will reach the end of their lifespans, as well as what kind of additional density is required in the upland to re-house those living along the shoreline. With a pathways approach, this visioning can guide near-term investments and restrict conflicting uses in a way that supports the longer-term vision.

Already, the city has decided to rethink siting a new school on low-lying public land along False Creek, and is undertaking a project to define “blue-green systems” for stormwater infrastructure that can be implemented along streets in support of the Sea2City vision.

Washington: Addressing today’s priorities as a driver for future visions

Washington state is involved in making systemic improvements to governance, funding and coordination to help shape coastal adaptation projects that address immediate needs and build long-term community resilience to coastal hazards.

Henry Bell, coastal planner at the Washington State Department of Ecology said, “We‘re doing a lot, including providing grant funding for local sea-level rise planning and vulnerability assessment projects. We are also in the early stages of the state rulemaking process to integrate sea-level rise planning requirements for local governments with marine shorelines, and supporting various local and regional coastal resilience project proposals for federal funding. Just last year, the state legislature provided ongoing funding to Ecology for a multi-organization coastal resilience team that is dedicated to helping small and underserved communities access funding opportunities for resilience work. We piloted this concept as part of the Resilience Action Demonstration Project between 2019 and 2021.”

Ecology recently received an $850,000 grant to partner with the Washington departments of Transportation and Fish and Wildlife, and Washington Sea Grant. A similar partnership between the Pacific Conservation District, Sea Grant, and Lower Columbia Estuary Partnership has supported a series of public workshops with affected communities centered on sea-level rise risks to help identify priorities and potential project opportunities.

“Our approach is based on finding where future conditions or changes overlap with today’s priorities,” explains Jackson Blalock from the Pacific Conservation District. “It’s harder for communities to dedicate limited resources to future conditions if they don’t also address an active priority, so this has helped get projects moving, instead of falling into a planning wormhole.”

It’s been said that it’s a privilege to think about the future. Equitable long-term visions acknowledge this reality – that planning must address the needs of capacity-limited communities that have experienced harm and disinvestment as the first step toward a better future where everyone can reap the benefits.

A long-term vision rooted in current priorities enables coastal adaptation work to be more than a Band-Aid, addressing future flood risk as one of many important objectives that improve the quality of life for affected communities today, and support the wellbeing of future generations.

“This has helped develop projects that break out of the disaster-response cycle and move toward more sustainable process-based approaches, such as collaborations that span property lines or jurisdiction’s boundaries,” Blalock said.

Coastal adaptation can have far reaching benefits for communities, prompting critical evaluation of design and planning processes, and leading to important shifts in the systems that shape the built environment. In the San Francisco Bay, the RSAP is setting the stage for regulatory shifts, regional alignment and cross-jurisdictional collaboration. In Vancouver, planning processes and visions support reconciliation with Host Nations, and define a path toward repaired shoreline relationships. In Washington, coastal adaptation efforts are identifying current needs of affected communities to drive investments that aim to improve present wellbeing, and shape better shorelines for future generations.