Date Posted: 08.05.2024

Colleges and universities across the nation are currently experiencing dynamic tension between long range development initiatives and disruptions in enrollment trajectories due to the declining birthrate, lower confidence in the value of a college education, FAFSA difficulties, shifting demographics and affordability barriers experienced by diverse student populations. Some regions and systems are grappling with growth and transformation while others are seeking to update campus infrastructure and facilities to support recruitment and retention. All institutions, however, are committing to more innovative and flexible ways to address student housing needs to better ensure the future success of their students and programs.

Three key patterns have emerged in our work with diverse public and private institutions to plan, design and construct vibrant campus communities. First, universities across the nation are increasingly focused on providing affordable housing options for upper division students through graduation. Institutions and their students are intimately aware of the necessity to build sustainably, and are increasingly prioritizing carbon and energy reduction, electrification, building for resilience, and creating supportive, healthy and inclusive environments. Lastly, many campuses are growing and expanding to their outer edges, necessitating efficient and smartly planned growth within limited land resources.

Retention of Upper Division Students

In decades prior to the pandemic, universities concentrated efforts on the recruitment and needs of first-year students. As post-pandemic cost inflation has exacerbated off-campus housing affordability, critical focus has shifted to upper-division accommodation. Importantly, a study by the University of Oregon found that “Students who opt to live on campus their first year and continue to live on-campus do better on many metrics of student success. They have statistically significantly higher cumulative GPAs, are more likely to remain in school, and are more likely to graduate than their peers that live off campus.” Institutions providing affordable housing solutions are aiming to keep their students on a path to academic success and resolve falling return rates for sophomores, upper division and graduate students.

As of January 2022, the UCLA Center for the Transformation of Schools reported that approximately 10% of its students experienced homelessness at some point during their academic career. Although these statistics can fluctuate over time, it has been found that COVID-19 has accelerated preexisting inequities present for students and families profoundly impacted by poverty and inequality in California. This statistic reflects a significant and ongoing issue in the region and surrounding university systems.

UCLA has built over 5,300 beds in the last five years to provide affordable housing on campus for all first-year students and increase on-campus living for upper division students. The university has also received external financing supported by State General Funds for the Higher Education Student Housing Grant Program to provide critical subsidized housing to its student body, a third of whom come from low-income families. The latest project in this initiative is UCLA’s Gayley Towers, a 562-bed, LEED Gold targeted urban infill project with a “vertically integrated” community, meaning the project will blend first-year students through seniors. It is an exciting example of the new residences that are increasing affordable options for upper division students.

The adoption of non-traditional unit types, apartment style and hybrid models allow future flexibility between undergraduate and graduate use. The affordable co-housing model of Gayley Towers is unique because it provides more flexibility for students to live independently. A generously sized community kitchen provides multiple cooking stations on each floor for students to prepare their own meals, allowing greater flexibility in meal plan options. UCLA will also support this style of living by providing “the basics” for cooking, whether milk, bread, olive oil, or fruit and vegetables. Additional storage space is provided in each individual’s living space for personal food items.

Gayley Towers at UCLA will feature vertical integration of first-year students through seniors. Design by Mithun.

Experiencing similar student demands, the Colorado School of Mines is reshaping the sophomore residential experience with an expansive new facility at the campus edge. Set to become the largest residential community on campus, this center will support sophomores’ transition into upper division independence with a mix of apartment configurations including individual and shared bedroom options. Built-in kitchenettes for every unit and a retail style dining hall on the ground floor empower students with accessible food resources and alternatives to traditional “dorm style living.” This strategy contributes to the university’s goals of ensuring long term affordability and choice for students.

A mixed program of ground floor amenities further includes an 8,500 sf fitness center, yoga/dance room with outdoor connection for classes on the lawn, multipurpose event/study room that can accommodate 100 students, and multiple social lounges with fireplaces. Student activity flows out to an outdoor courtyard and recreation field from connections at the dining, lounge and fitness spaces.

Flexible dining and lounge areas, group studies and a fitness center enhance community cohesion and student retention. Design by Mithun in association with Anderson Mason Dale Architects.

Today’s generation of students have also arrived on campus with a broad spectrum of challenges, including academic stressors, added pressures of recovery from a pandemic, the daily intensity of news and social media, and, in general, more mental health challenges. The result is the need to provide a broader differential of facilities that support academic success and, for us, as designers, to create places within a framework that best support the health, well-being and overall sense of belonging for students. To address this, many new facilities integrate academic and partner program spaces, such as Academic Residential Communities at the University of Oregon; counseling resources, included in our work at UC San Diego; meditation rooms newly designed at UC Irvine; and other health-focused support elements, such as music facilities at the Colorado School of Mines. The increasing complexity of student need has also driven a broader unit mix into many recent projects, with a larger proportion of single occupancy units in combination with larger suites and apartments.

High Performance Design and Delivery

Mounting pressures to address the complex housing needs for students and institutions comes at a time when construction cost escalation and residual pandemic impacts such as trade partner availability and supply chain challenges have ratcheted construction costs to unsustainable levels. Although we are now seeing a softening of these pressures, institutions are seeking different design and construction delivery methods such as design-build, public private partnerships and integrated delivery to help bridge economic gaps, including renewed interest in prefabrication and systems innovation.

The emergence of mass timber, prefabricated and unitized cladding systems, and other time saving approaches have enormous relevance to student housing. Optimum short structural spans and repetition of systems and modules allow an accelerated project schedule. The regularity of framing in mass timber provides both speed to erection as well as demonstrated biophilic and mental health benefits, amplifying institutions’ mission to support student wellness, beyond the savings in carbon and time. While there is inexplicable friction with builders’ risk insurance and other market forces, mass timber and other non-traditional innovations continue to take root in new construction projects in part or whole.

Another key area of innovation has been envelope design and energy performance as campuses look to reduce operational costs and carbon over time. Passive House, one of the most stringent energy performance metrics currently available, has been adopted by Princeton University and Georgia Institute of Technology on two new recent housing projects. With a high-performance envelope and building systems, Princeton University’s new Meadows Apartments is home to 604 graduate students and one of the largest Passive House certified projects in the country .

Sustainability synergies span Princeton University’s Meadows Campus, including rain gardens and green infrastructure, geothermal exchange wells, reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, carbon sequestration and use of low-embodied-carbon materials. P3 delivery in association with American Campus Communities.

The south’s first Passive House living learning facility, Georgia Tech Curran Street Housing will serve as a visible campus edge symbol of sustainability and innovation. Smart massing and a high-performance envelope with a modular approach to exterior skin will provide lower energy use in a climate with a high cooling demand. These sustainable strategies are accompanied by stormwater management and ecological design concepts that seamlessly integrate the project with Georgia Tech’s central Eco Commons, fostering ecological function and health.

Creating a new welcoming portal at the east Edge of Georgia Tech’s Atlanta campus, this project serves as a visible campus edge symbol of sustainability and innovation to the greater community. Design by Mithun in association with Lord Aeck Sargent.

Increasingly, building at the highest level of sustainability matters to the current generation of students. Recent Post Occupancy Evaluation (POE) work at several campuses reveals the importance of living in a facility that is proactively addressing the current climate challenges that this generation is inheriting. UC Irvine’s latest expansion to the successful Mesa Court neighborhood, Oso Tower adopts the community’s holistic approach to sustainable design. Universal accessibility, indoor air quality with CO2 sensors, healthy materials, active stairs and trail access support a health-positive experience for students. The LEED Platinum target design reduces energy consumption and its carbon footprint by harnessing prevailing winds and solar energy. Comprehensive stormwater management, bird-safe design strategies and ecologically sensitive plantings support the adjacent natural marsh habitat and shifting climate patterns.

UC Irvine Mesa Court Expansion’s LEED Platinum target design leverages solar thermal power generation to reduce energy consumption, incorporates sunshades and high-performance glazing to reduce heat gain, and reduces stormwater run-off to below pre-development rates in support of water quality in the regional ecosystem. Design-build project delivery in association with Webcor.

Porous Campus Edge Transitions

Highly saturated or infeasible sites in campus cores along with limited remaining land resources, have resulted in the transformation of campus edges. With the need for additional and updated housing options, many campuses are finding these remaining parcels of land are needed for additional student beds. The introduction of significant density and scale at these campus boundaries necessitates a range of new considerations by higher education institutions, including new collaboration with surrounding neighbors and communities, as well as planning and programming for mixed internal, or institution-focused, and external, neighborhood use. The last decade has seen an erosion in the idea of a hard line between campus and city, and a more blended ecotone where community participation in the campus is both welcomed and intended.

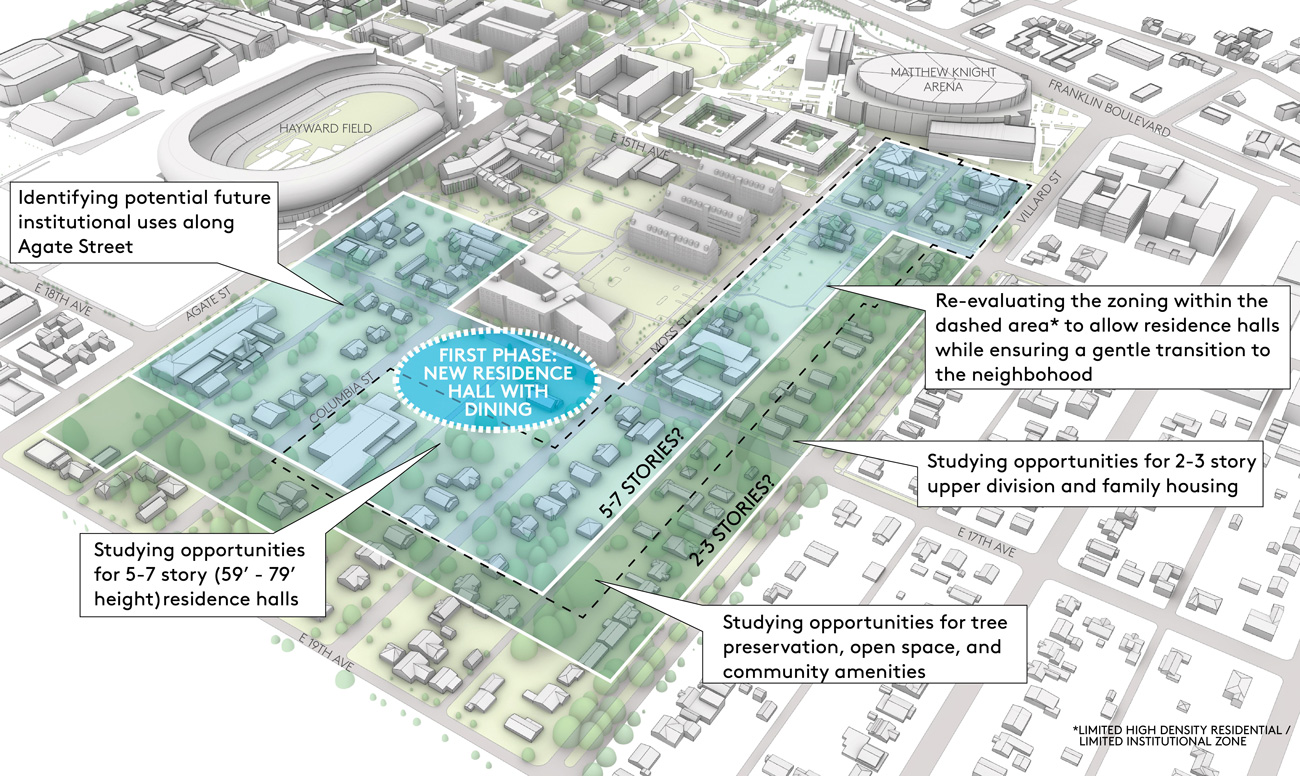

The University of Oregon Next Generation Housing Development Plan and East Campus Framework utilizes a district-scale approach to planning, emphasizing public realm and urban design thinking to support the campus’s growth. The east campus is one of the few remaining areas of underutilized land at the University of Oregon, and this planning work helps understand and realize both the capacity for new housing options along with the best use, scale and relationship to the surrounding Eugene community. A feathering between new faculty and graduate use at the campus edge provides a gentle transition between the adjacent Fairmont Neighborhood and the higher density, first-year and upper-division housing that are planned on the more interior layers of this new precinct.

These campus edge sectors often require subset master plan and infrastructure strategies as new facilities are either subject to city standards for zoning and rights of way or out of reach for campus energy loops. Oregon’s Next Generation Housing is being planned to connect to a new internal campus energy loop, eventually powered by a new central utility plant to be developed in future phases of construction. The new campus gateway and precinct project is studying how to adapt the existing regular grid of right-of-ways to create updated circulation routes and open spaces that will serve as a future neighborhood public resource.

The University of Oregon’s East Campus Framework is founded on the idea of a “Gentle Transition,” allowing building scale and open space to gradate down to the adjacent residential and commercial scale. Planning by Mithun in association with Rowell Brokaw.

The University of Montana Residence Hall is a new student housing community on a prominent public corner of the campus that will “bring down the brick wall” between the university and Missoula, and provide a welcoming gateway to campus life. Once complete, the 690-bed facility will be the largest housing facility on campus and first new building for student life in over four decades.

Façade materiality reflects the area’s natural history, drawing inspiration from the ancient strandlines seen on Mt. Sentinel. Design by Mithun in association with MMW Architects.

This gateway project will stand in place of an existing parking lot, with pathways and connections through campus to the adjacent K Williams Natural Trail Area, the iconic “M” and Mount Sentinel regional space. Both marking the entry to campus as well as recognizing the scale of the adjacent neighborhood, the project is thoughtfully set back from the street, bringing human scale and natural materials down to the ground and pedestrian level. Landscape design will engage and celebrate the community, local ecology and the university’s distinction as a state of Montana arboretum.

Looking forward

Universities will continue to encounter challenges as we face the progressive impacts of climate change, shifting demographics and emerging technologies. Design and construction innovation can substantially help higher education institutions thrive amid these challenges, supporting future flexibility. The solution to these myriad questions is not straightforward, but we know that adaptable environments for student life will play a foundational role, grounding students and educators in a collective future.