Organizing Refuge Alongside Community

Vision

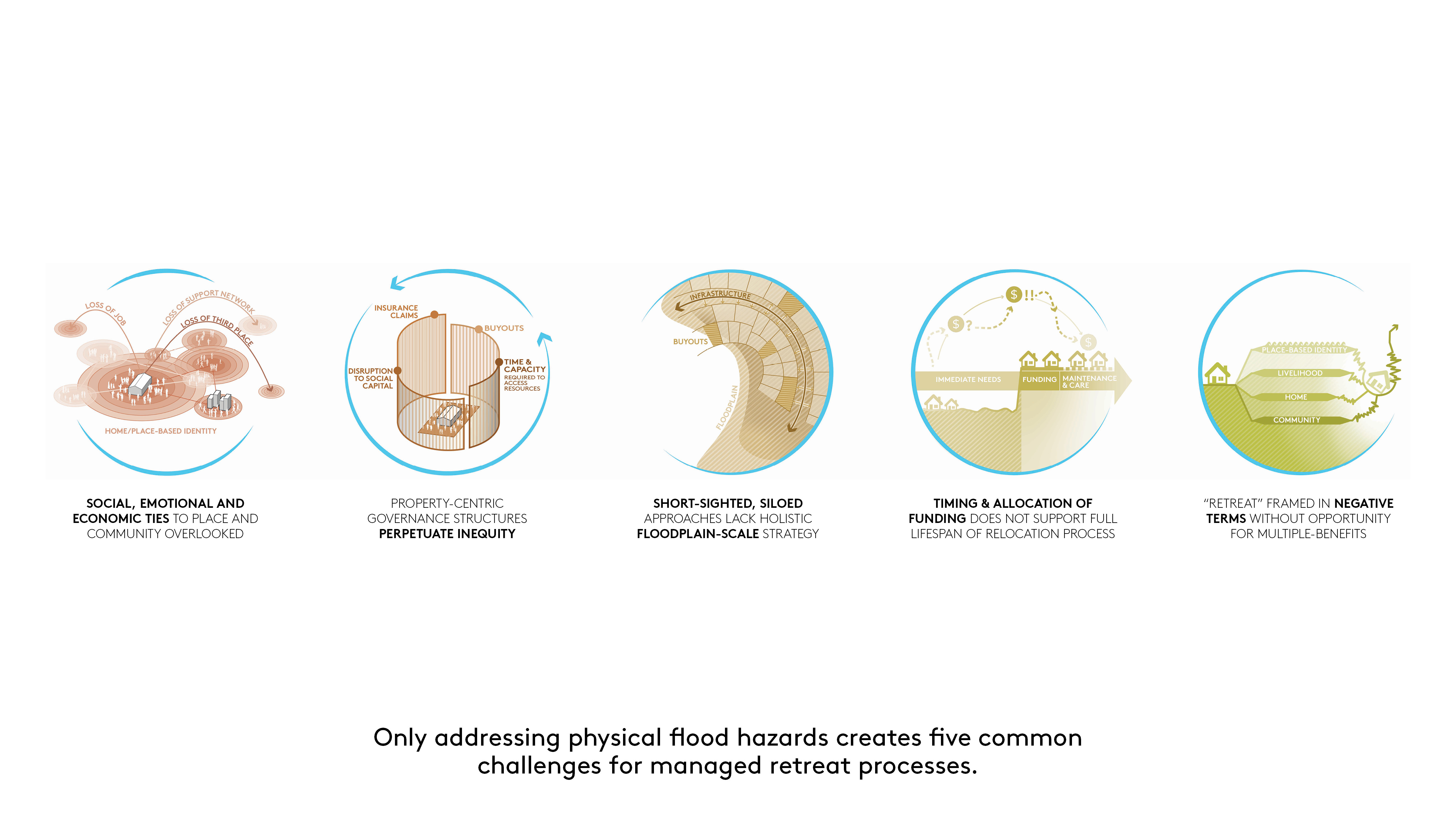

‘Managed retreat’ is the movement of populations and infrastructure away from hazard zones (Reidmiller et al., “Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States: The Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume II.”). Though the language may make it sound neutral, this is a complex, political and deeply personal process for those impacted. By 2100, as many as 13.1 million people in the United States could be at risk of displacement due to sea level rise. In contrast, the primary funding entity, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), has acquired tens of thousands of flood-prone properties since 1989. The massive scale and inequitable distribution of flood risk in the U.S. demands a critical look at the process of managed retreat, which will increasingly need to be considered as sea levels rise. What are the challenges? How can equity, care and self-determination inform new approaches to this work?

Research

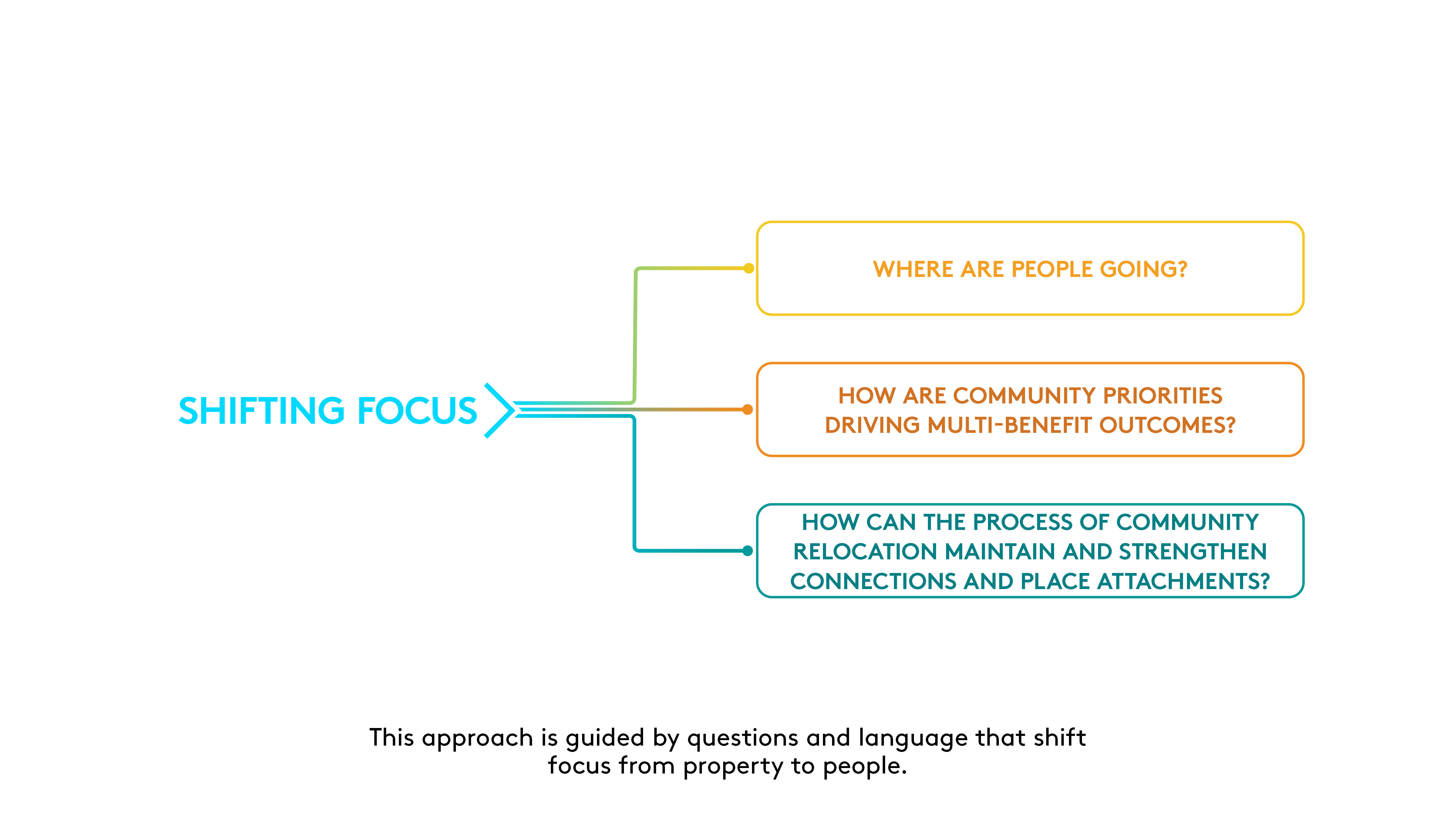

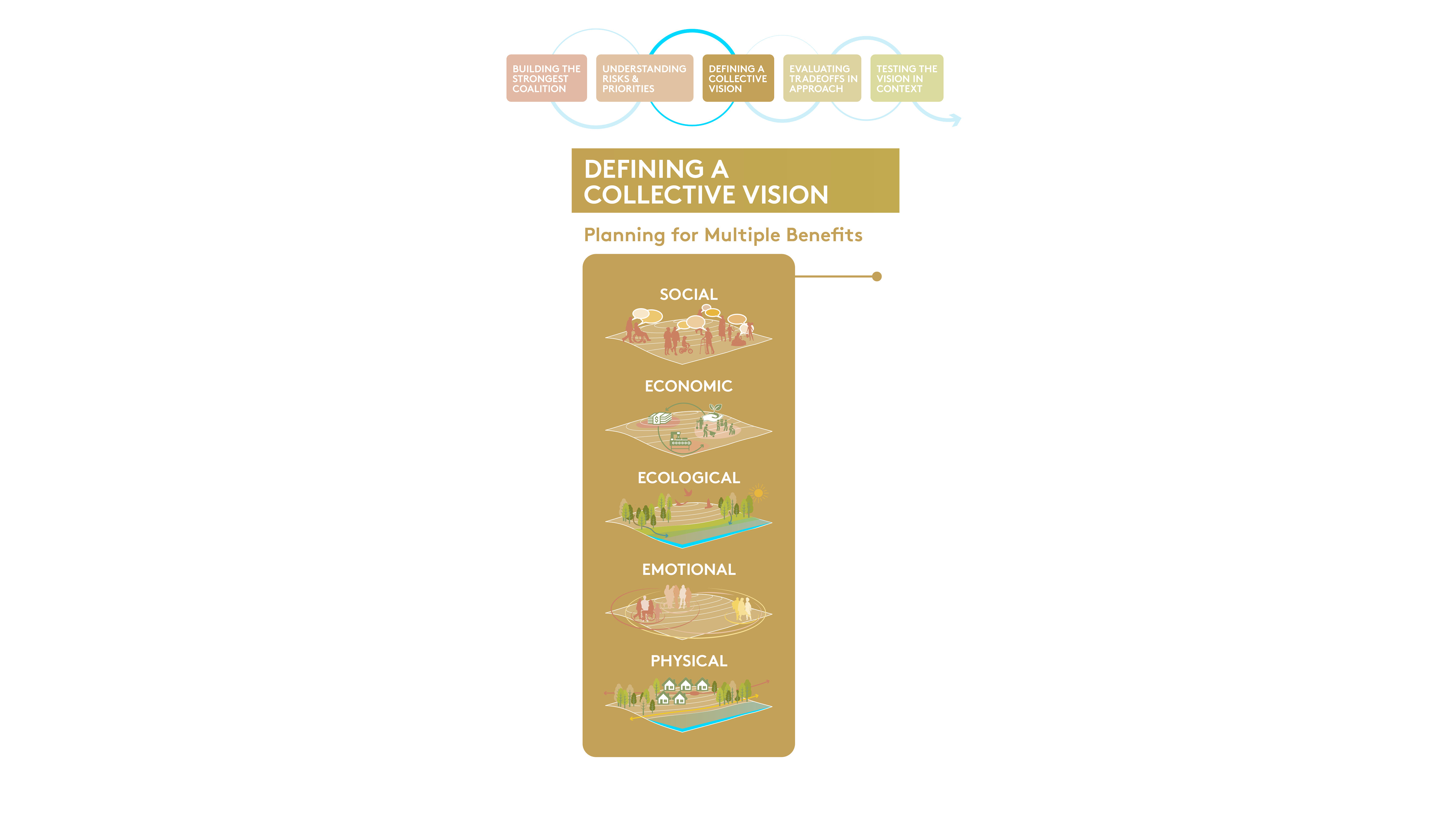

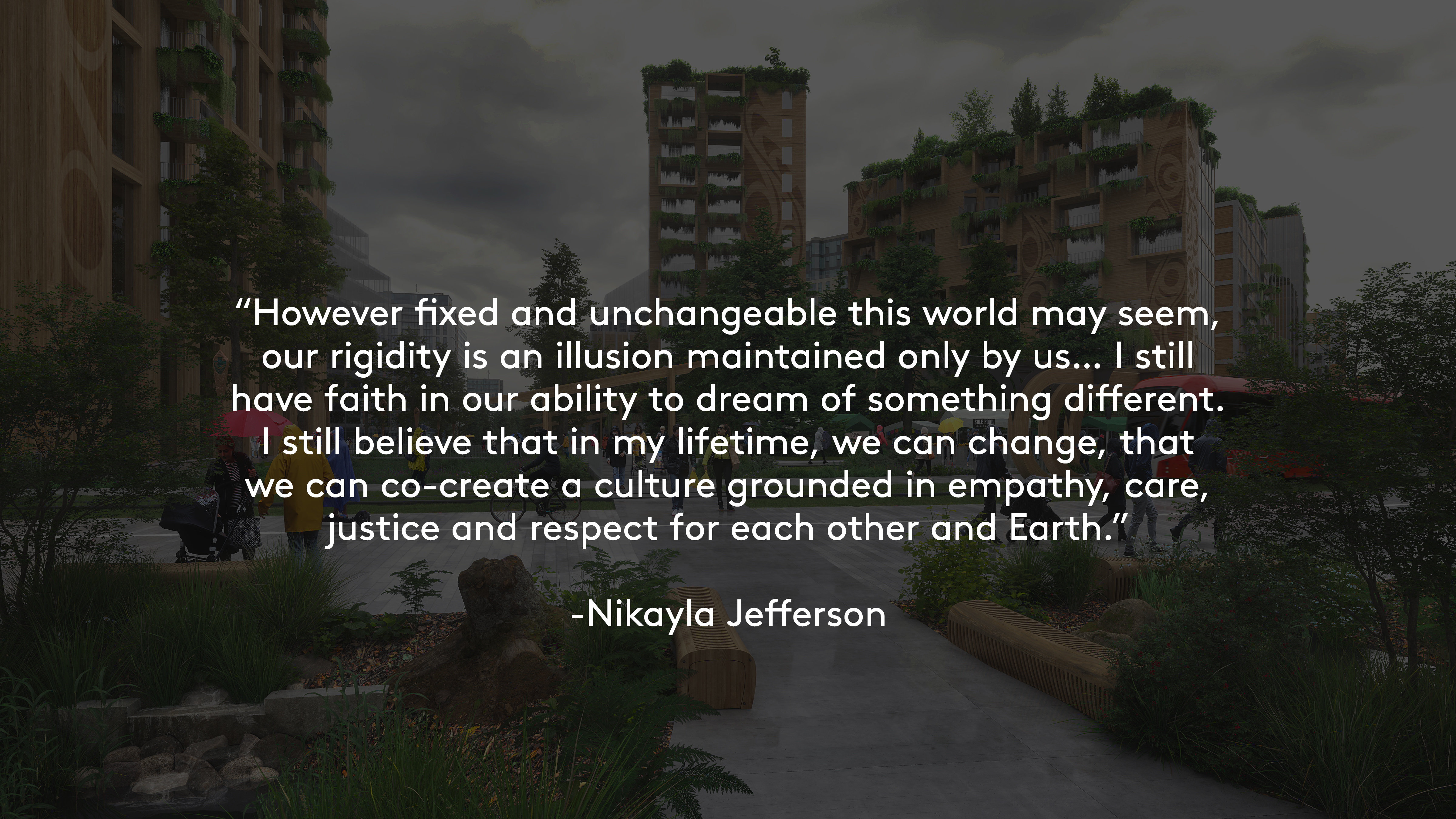

Equitable approaches to managed retreat acknowledge the role of past harm in shaping present hazard, and contribute to agency, reparations, and healing for impacted communities. This work aims to center justice and equity by shifting focus from property to people—from retreat to refuge. Where are people going? How are priorities of under-resourced communities driving multi-benefit outcomes beyond flood protection? How can the relocation process maintain and strengthen place attachments, economic opportunities and adaptive capacity?

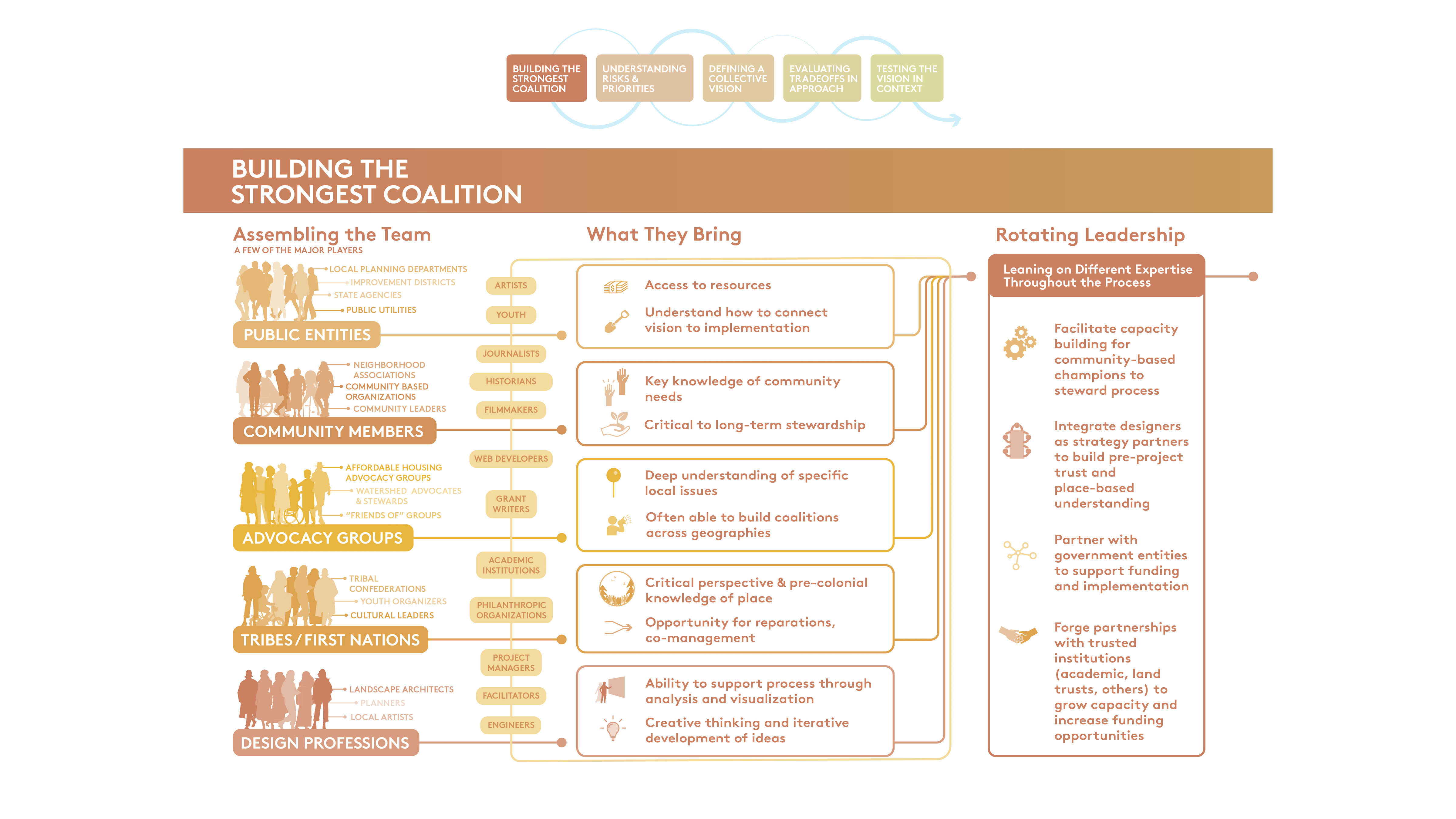

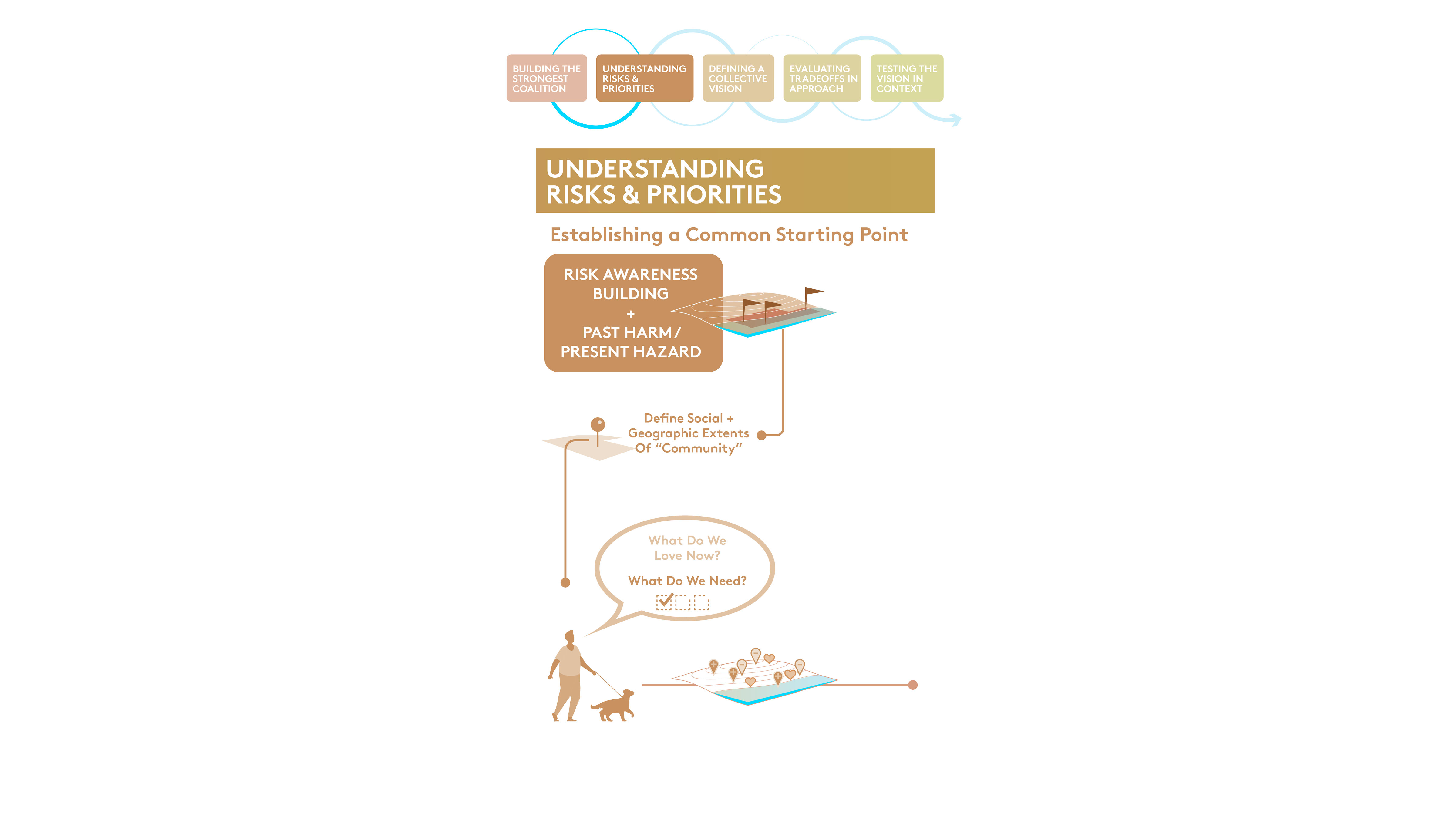

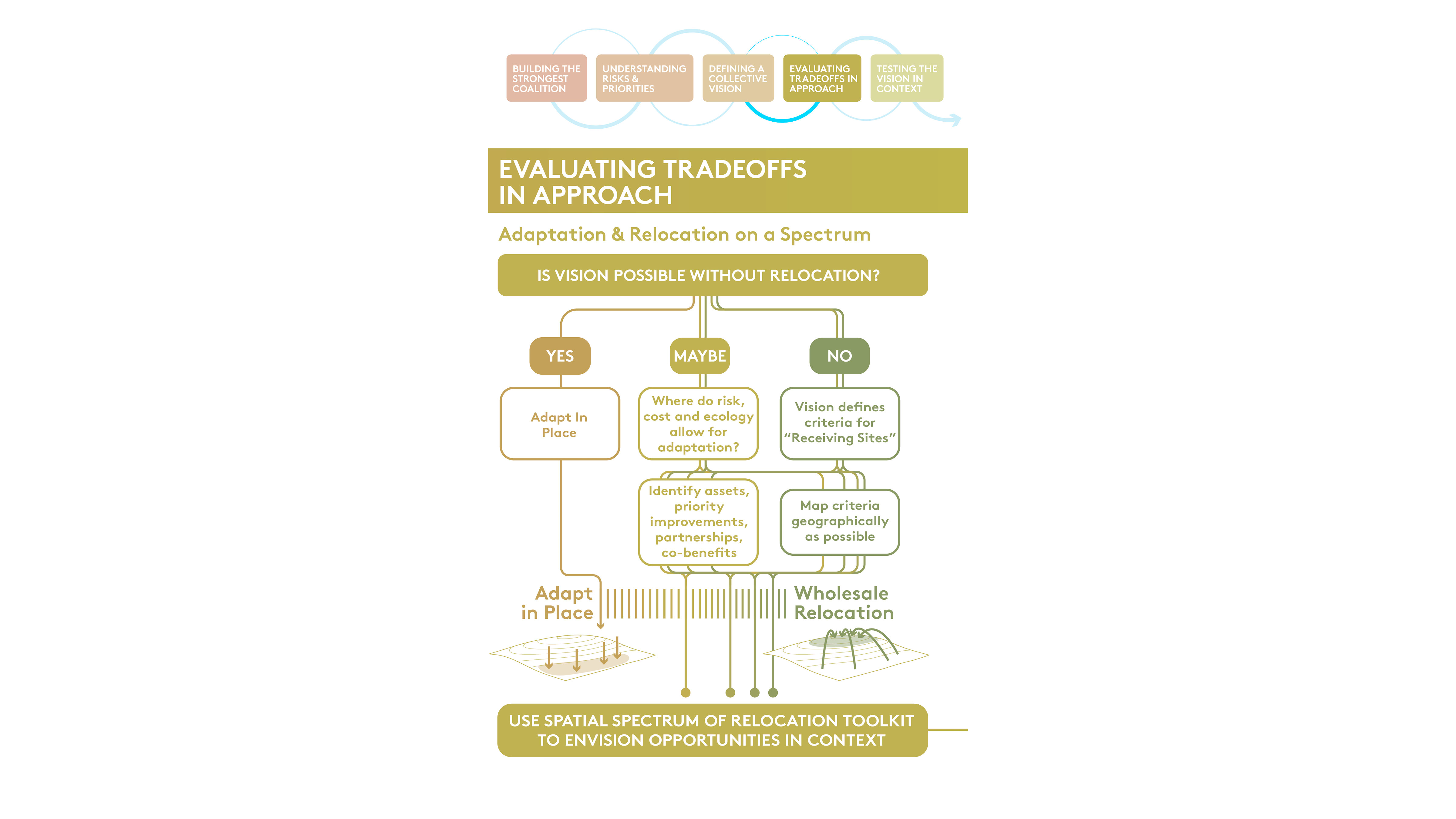

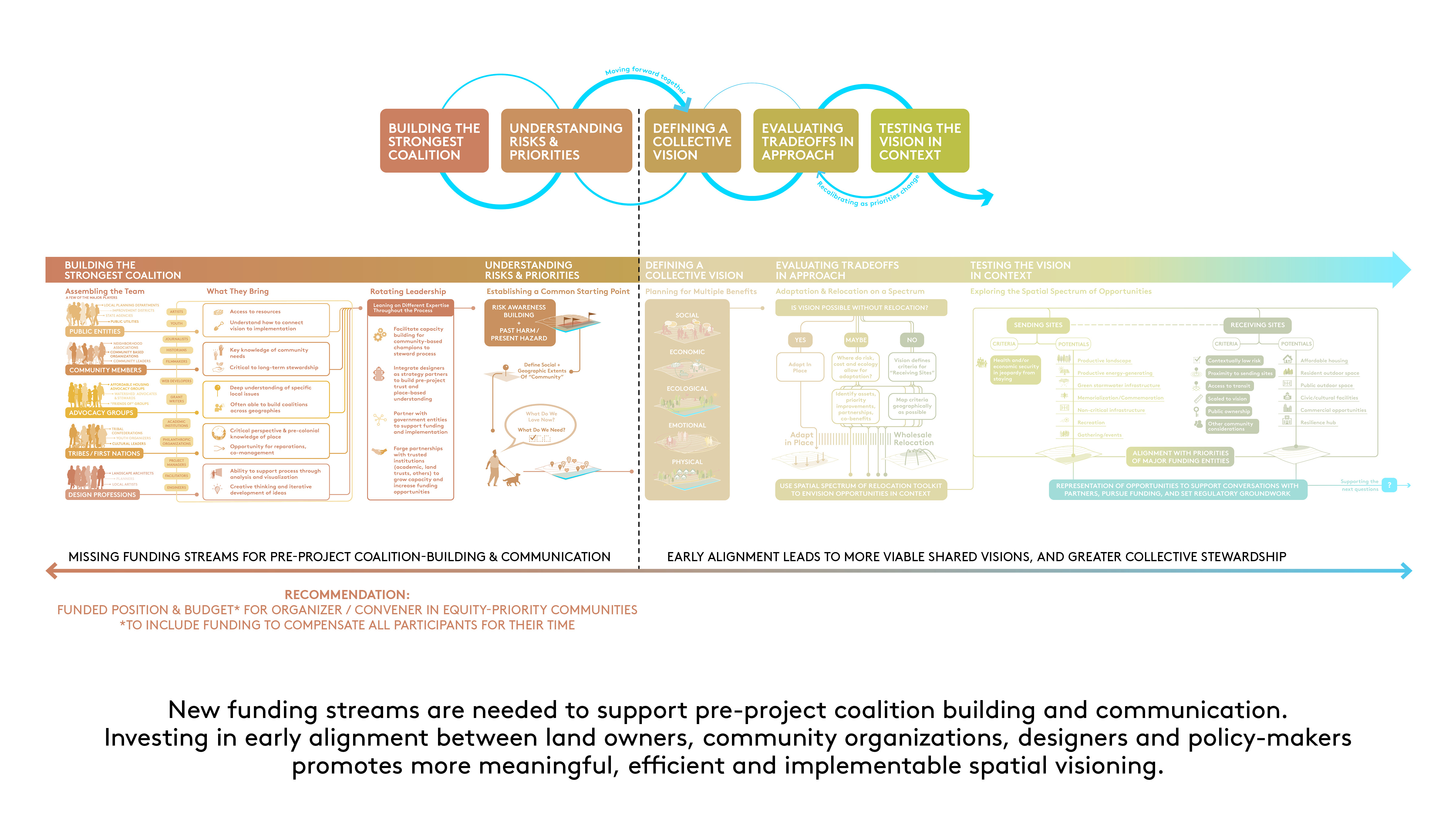

Unpacking these questions began with background literature research and interviews with practitioners and academics who have considered implementation, funding and other aspects of managed retreat processes. Combining these findings with learnings from other project types led to development of a spatial framework for envisioning place-based opportunities along the full adaptation/relocation spectrum.

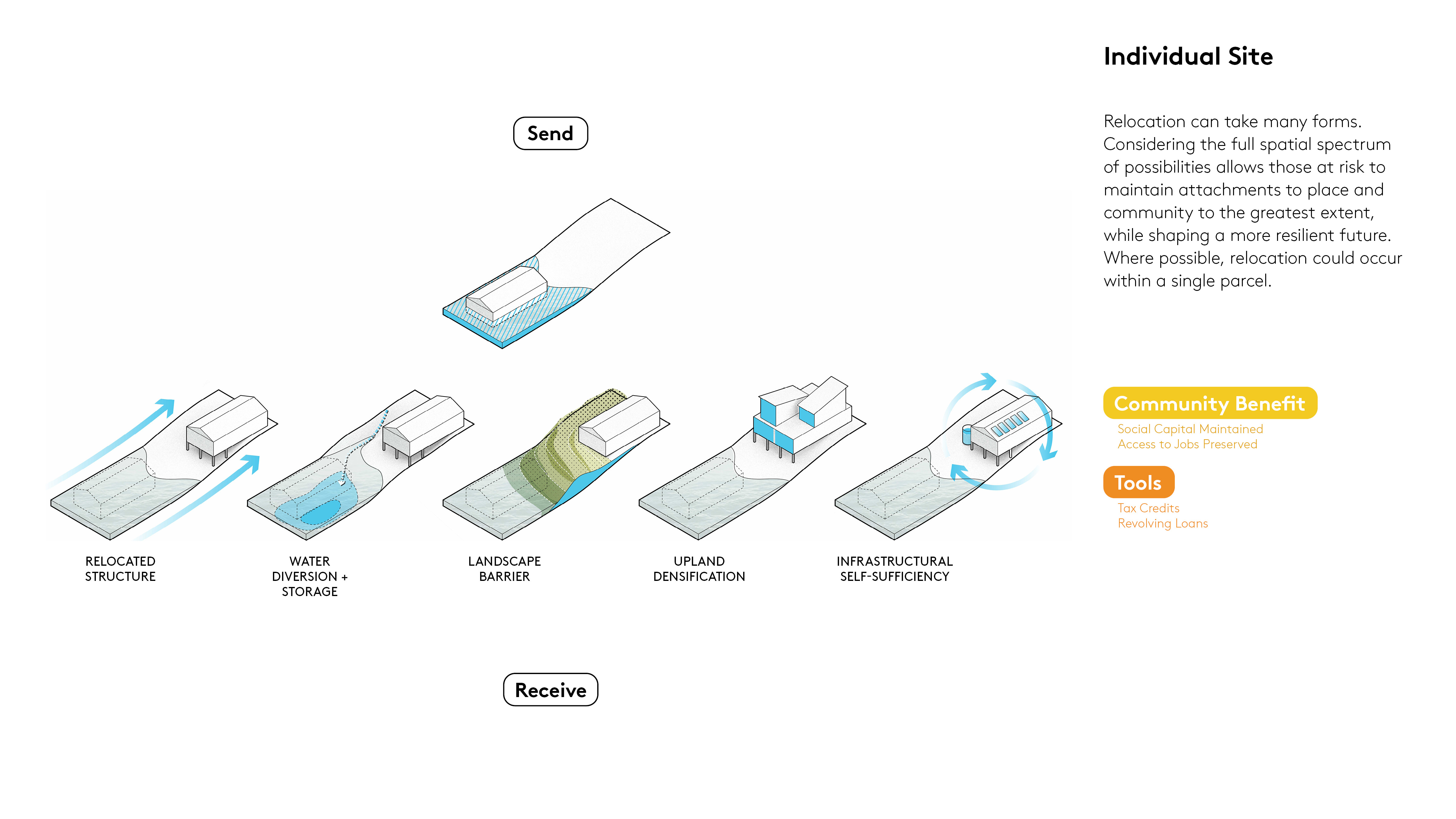

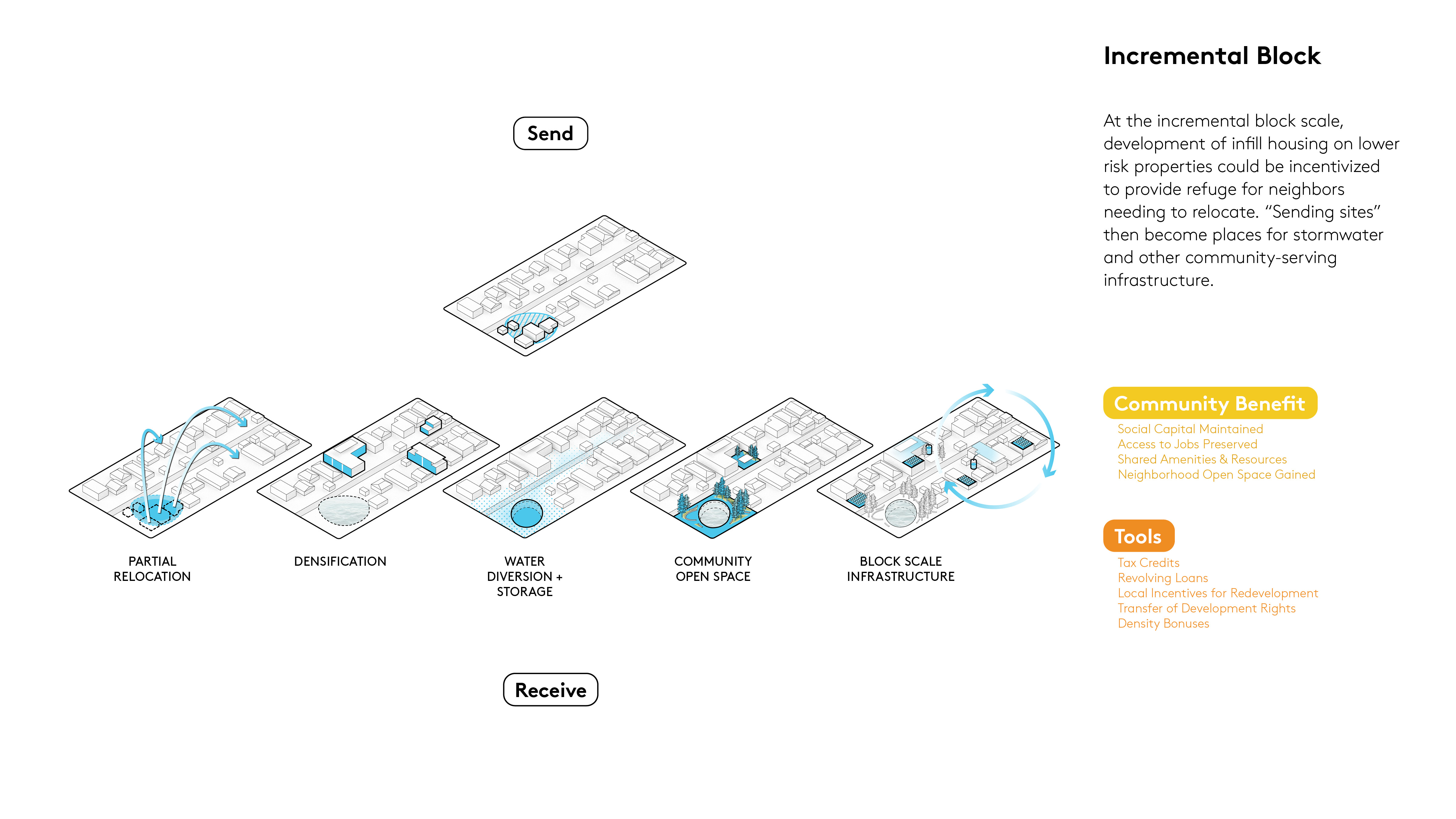

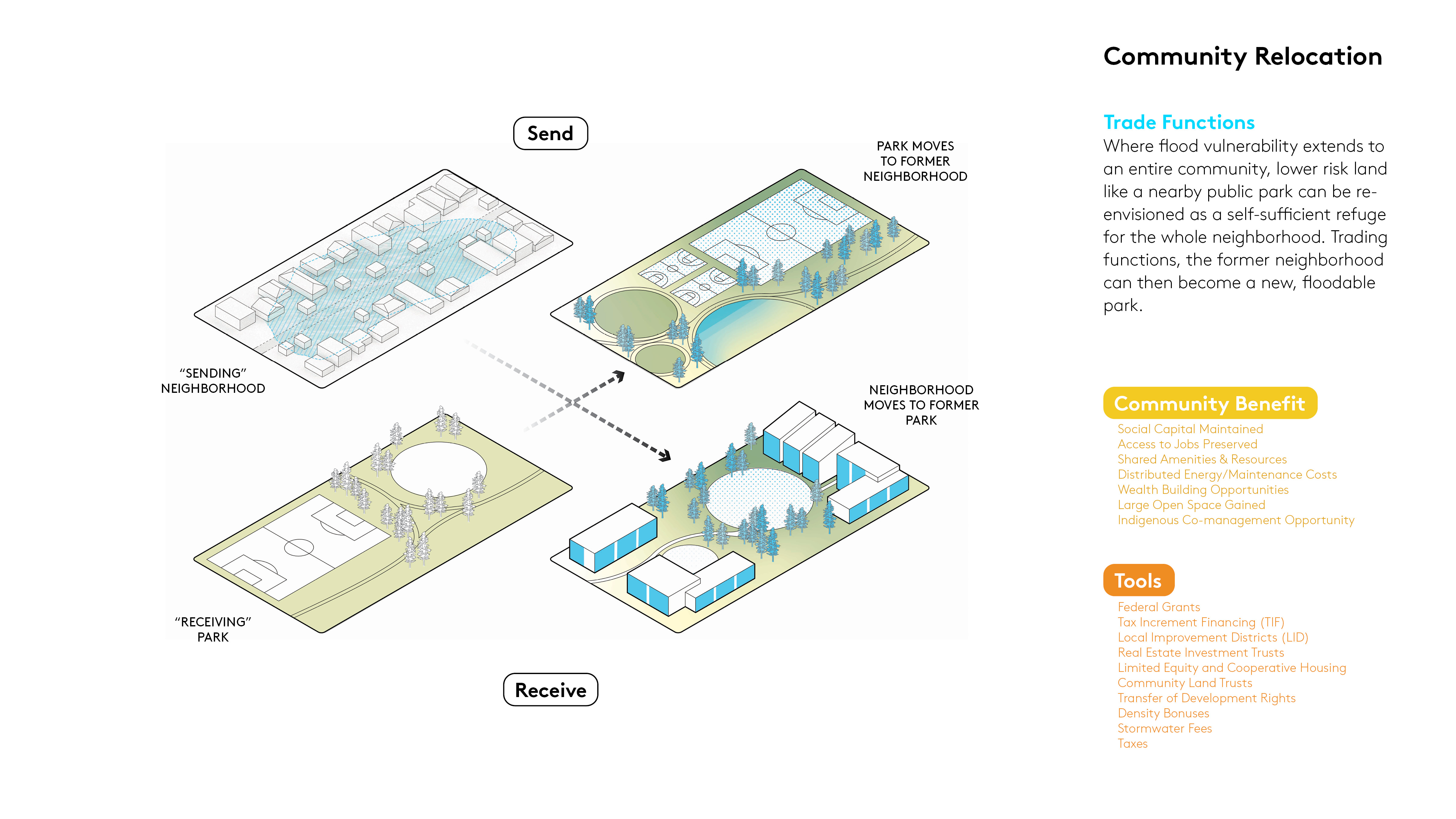

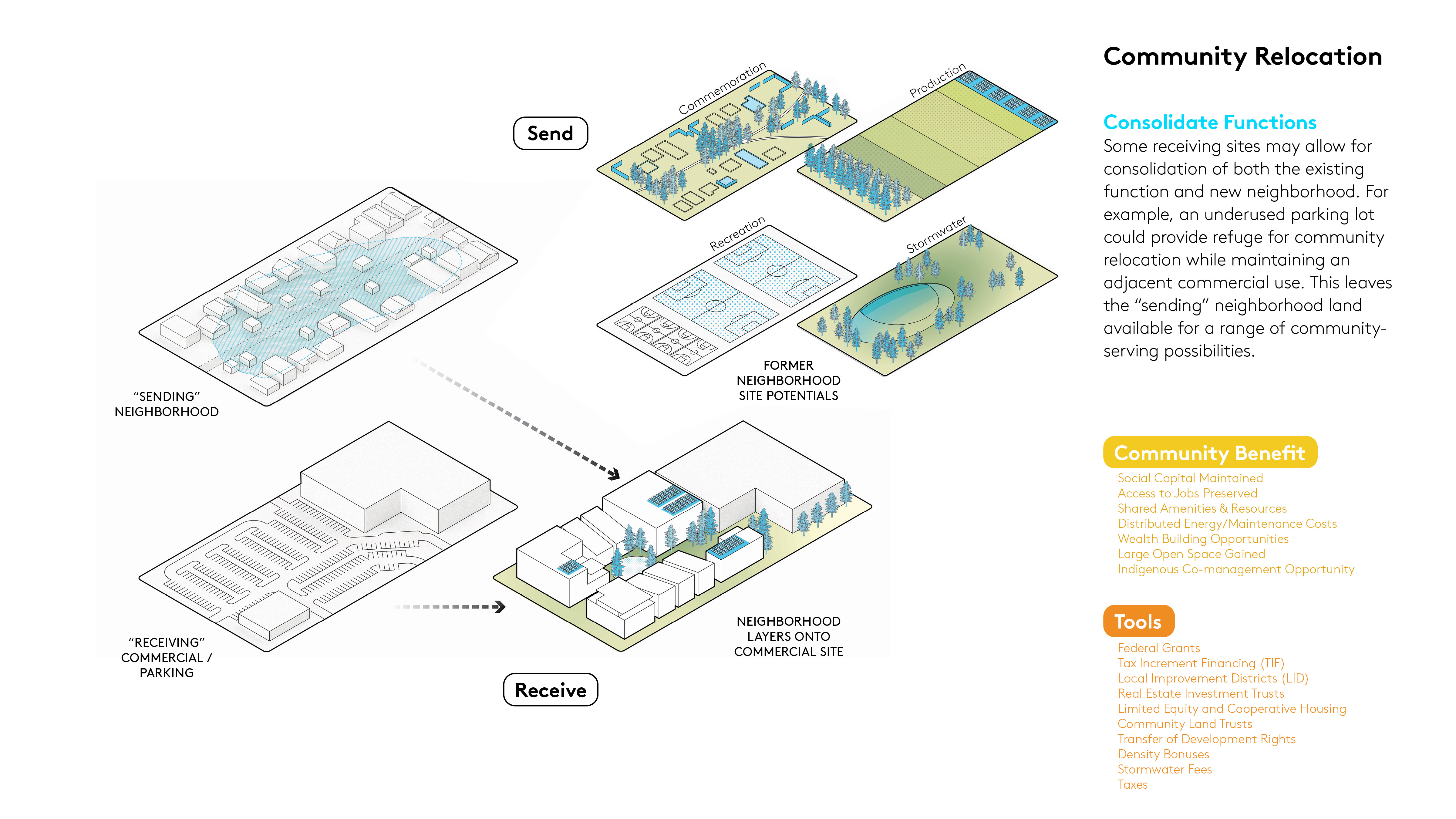

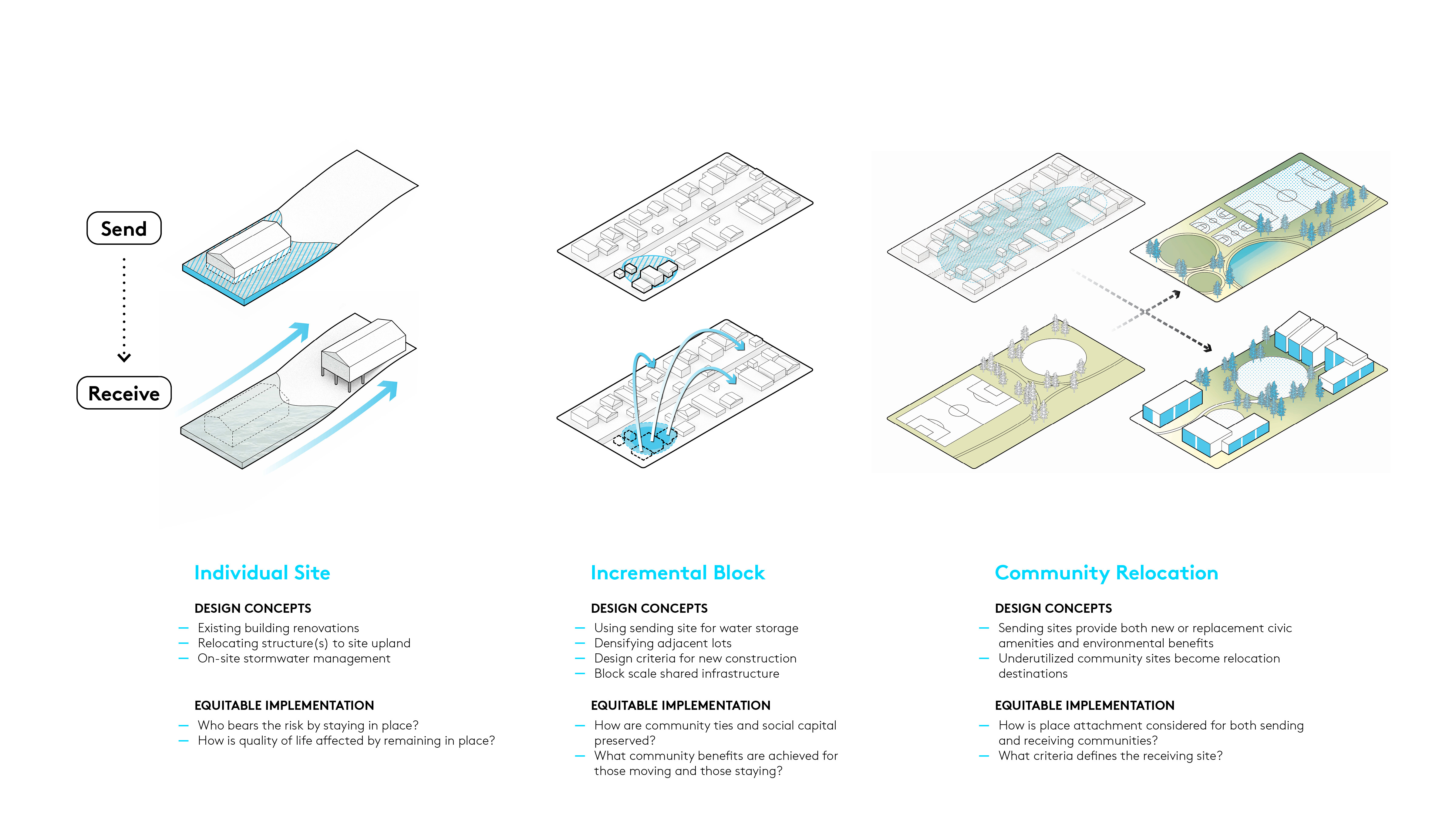

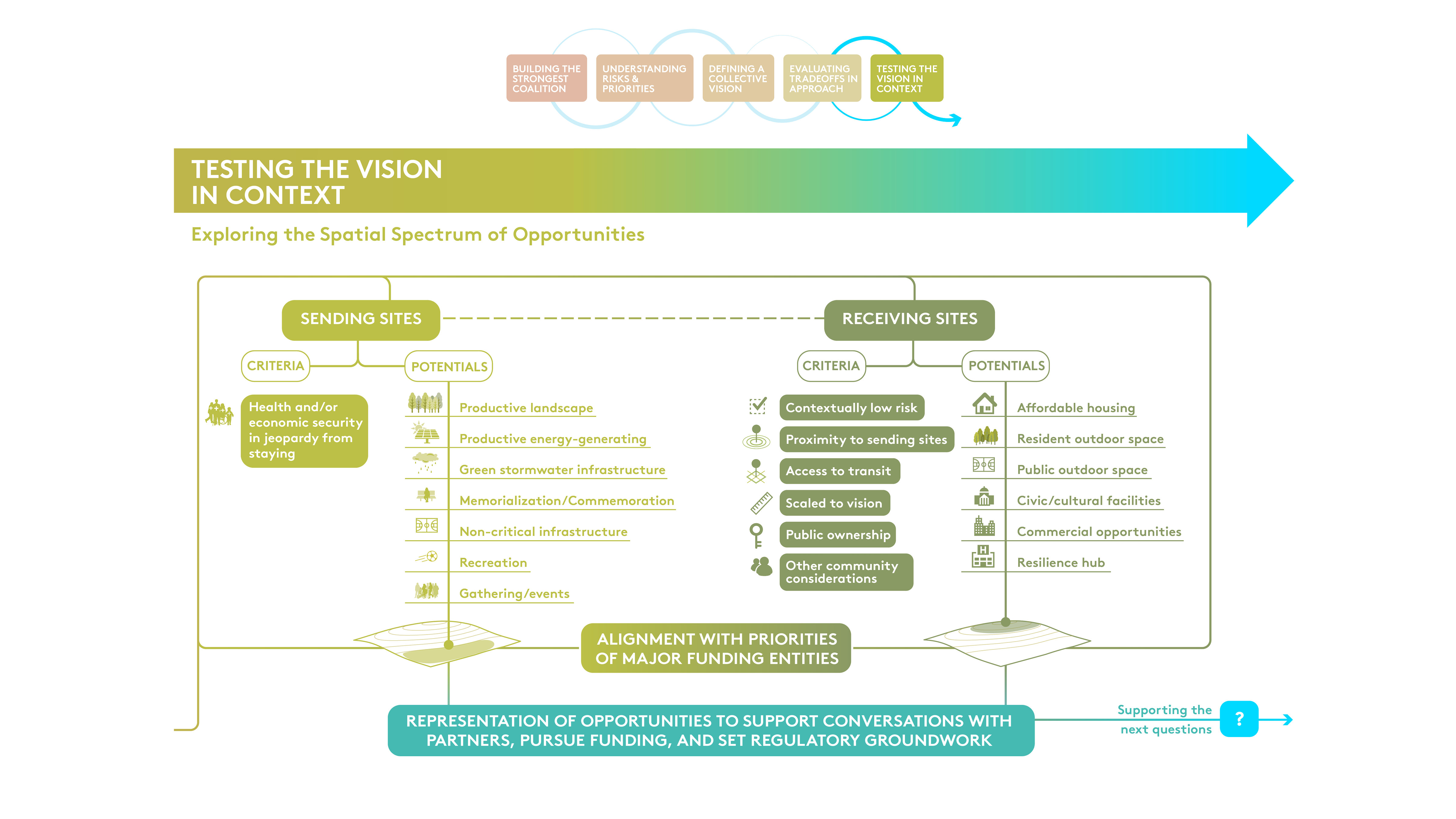

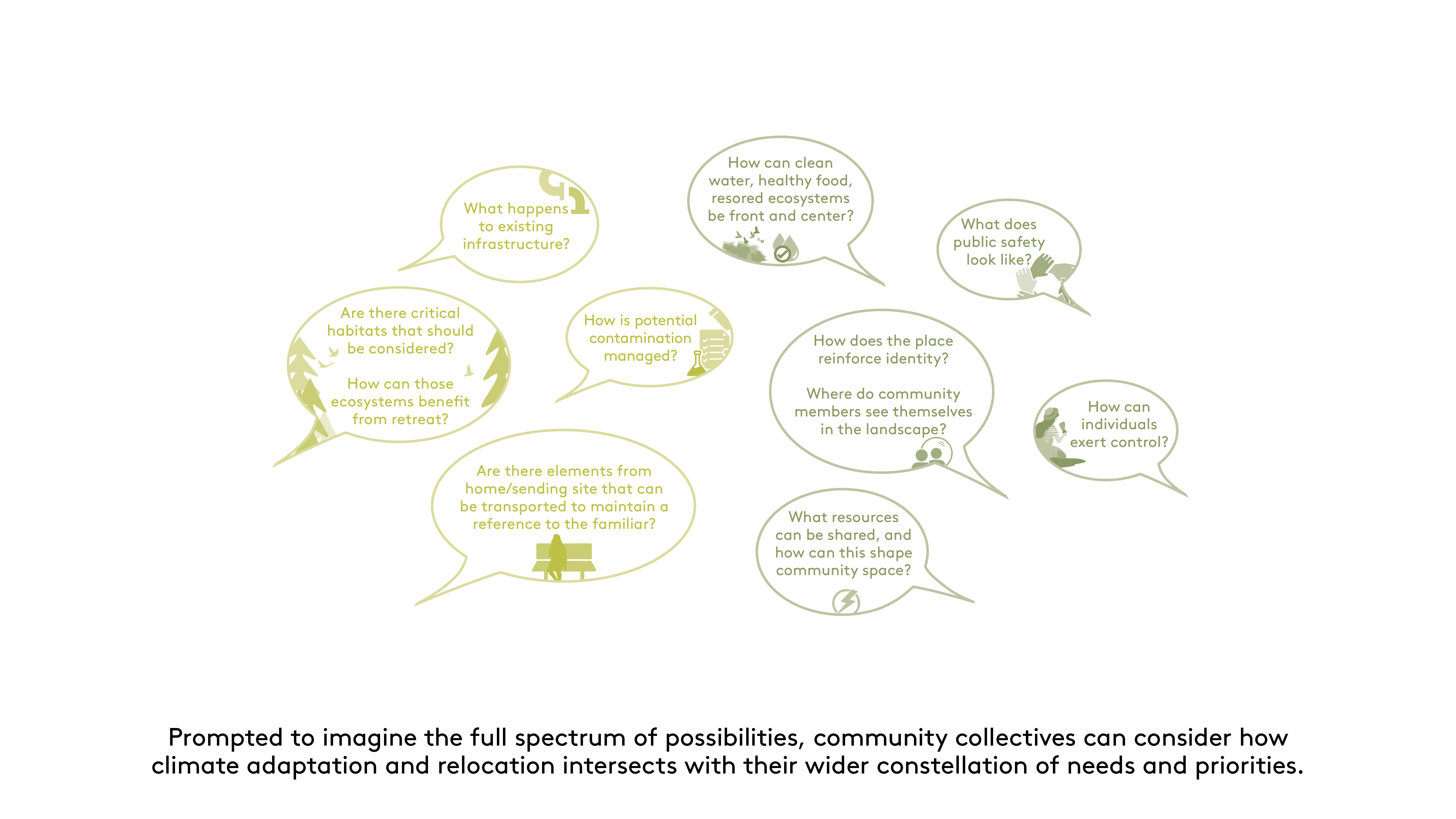

Considering the full spatial spectrum of possibilities allows those at risk to maintain connections to place and community to the greatest extent, while defining what a more resilient future looks like for them. To aid this effort, conceptual illustrations show the varied forms relocation could take across land ownership and spatial scales—within a single parcel, incrementally across a block or at a community scale. An equitable process flowchart was then developed to guide the application of these concepts in support of unique community visions for multi-benefit climate adaptation.

Looking Forward

Ultimately, we hope that coalitions of community-based organizations and designers can use this framework as a prompt, and together define a contextually nuanced vision for sending and receiving sites that responds to local hazards, place-based identities, access to jobs and social capital, resilient shared infrastructure and other community priorities.

The Sea2City Design Challenge in Vancouver, B.C. provides an example translation from concept to multi-phased site-specific vision that overlays multiple stakeholder prioritizes, including: commitment to decolonizing the design process, protection of sending site housing stock within its lifespan, restoration of pre-colonial shoreline habitat, co-stewardship of sending sites with First Nations and alignment with city-wide planning efforts.