Date Posted: 10.21.2025

Middle housing is emerging in places that have long resisted change. These residential buildings — smaller than apartment complexes but larger than single-family houses — include a variety of housing types like duplexes, townhouses and cottage clusters. As states like Washington, California and Oregon mandate that cities allow middle housing on all residential lots, public debate has surged.

There are real tradeoffs. Some worry neighborhood character will change as taller, bulkier buildings appear along familiar streets. Others fear the loss of trees from redevelopment. Many residents are anxious about parking or car break-ins with more street parking. And some want their neighborhood to remain unchanged, or fear change they struggle to visualize.

But there is also plenty to be excited about. Middle housing introduces more attainable housing options into single-family areas, mostly through shared land costs and smaller unit sizes which can be purchased or rented at lower prices. During the current housing crisis, attainable housing production remains middle housing’s essential contribution.

Middle housing can also increase choice by offering a variety of unit types and configurations that better match the diversity of housing needs. It allows neighborhoods to welcome people with different backgrounds, incomes and household types, and it gives residents options to stay in their community as they age or live in multi-generational arrangements. Smaller, more affordable units in higher-income areas create access to quality schools and amenities. Fee-simple ownership expands opportunities to build wealth through homeownership. Environmentally, middle housing supports growth within urban areas by making efficient use of infrastructure, reducing pressure to sprawl into rural and natural lands.

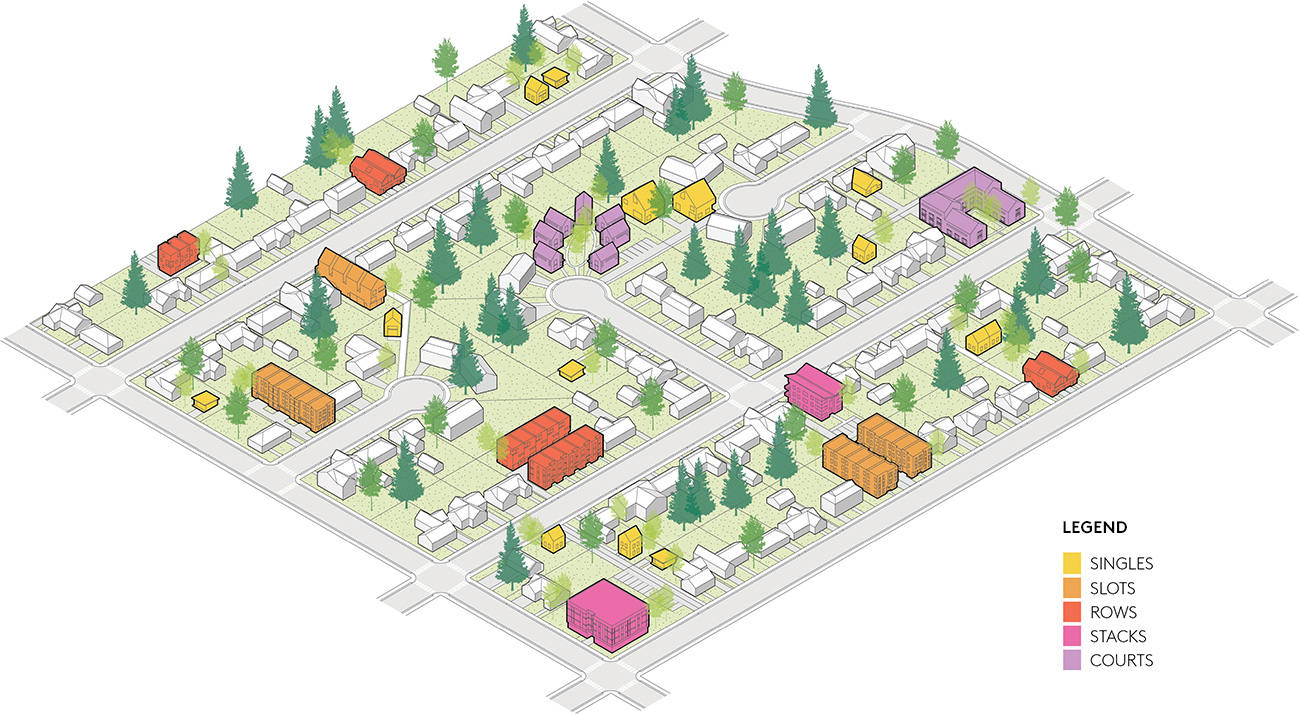

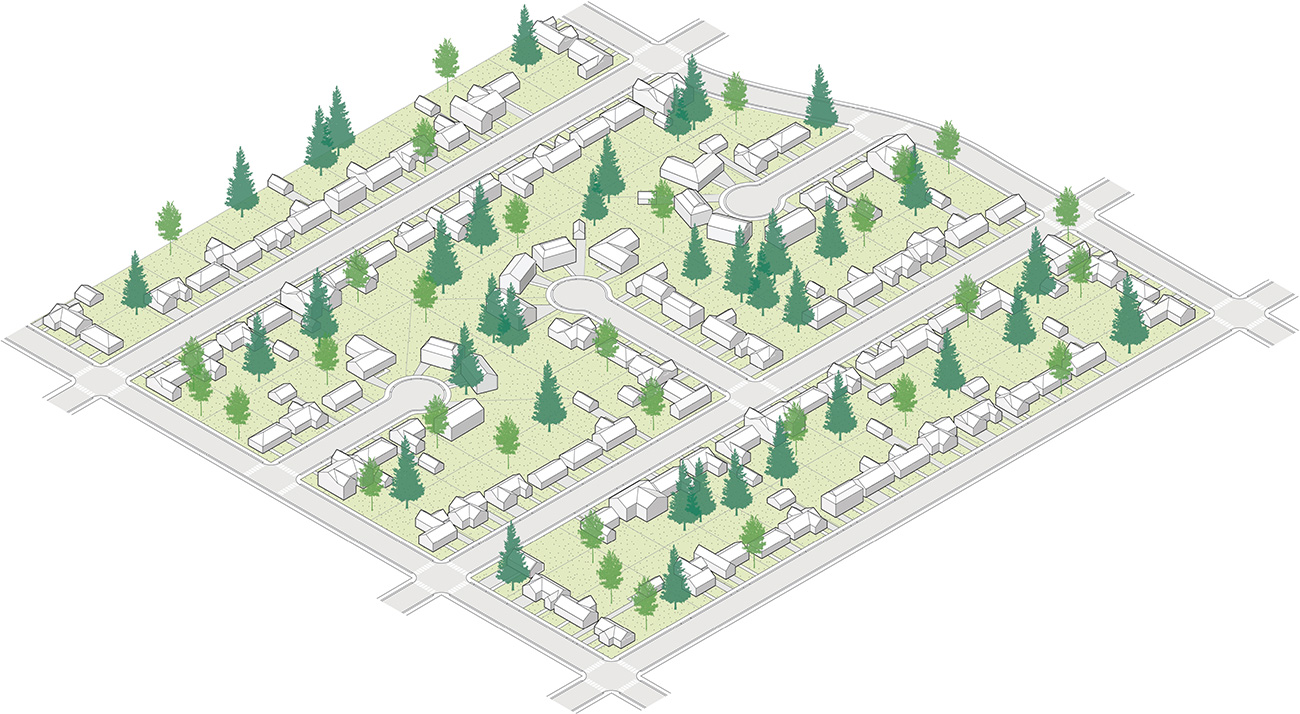

A redeveloped middle housing neighborhood envisioned for Tacoma using “Home In Tacoma” zoning, landscaping, and design standards by Mithun.

As cities update codes under new state laws, or revisit them over time, these benefits are achievable. But opportunities can be lost if emerging middle housing neighborhoods aren’t understood as complete organisms when they transform from single-family patterns into something more complex.

For decades, the dominant development pattern has been one house per lot, with private yard and garage. This template exists across income levels and is deeply familiar — builders know how to deliver it quickly and efficiently. While middle housing is physically compatible with single-family neighborhoods, treating it the same misses the chance to imagine more complete, people-centered places. Without a larger vision, middle housing can become isolated and inconsistent, then set in place for generations. As the paradigm shifts to denser living, we should think holistically about the future of these neighborhoods.

A redeveloped middle housing neighborhood envisioned for Mountlake Terrace, WA using zoning and design standards by Mithun.

At Mithun, we believe middle housing can do even more. Drawing on two recently completed codes (Home In Tacoma and Mountlake Terrace Middle Housing Code) and our upcoming Middle Housing Playbook research effort, we see four key ways to leverage middle housing codes for broader public benefits of design quality, health, sustainability and connections while also increasing production to meet urgent housing needs.

1. Design Standards to Support Healthy Living

Mountlake Terrace sought to incorporate walkability and human scale elements that complement neighborhood character into its new middle housing code. To do that, we paired Residential District Standards addressing height, bulk and scale with Design Standards that regulate orientation, transparency, entries, modulation, amenities and housing-type–specific features. The design standards were intended to ensure that middle housing would not just add units, but also support a stronger pedestrian experience and livability in the city’s neighborhoods.

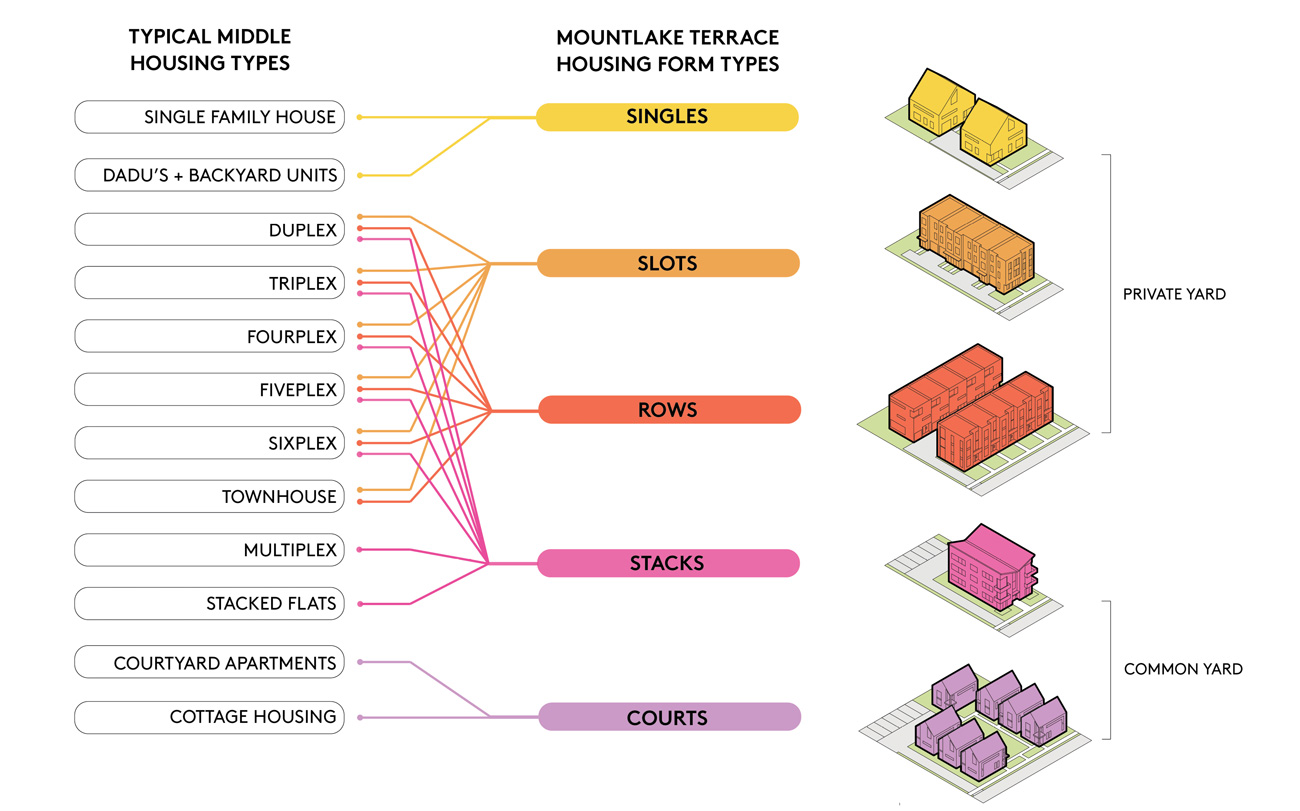

A key move was defining five housing types not by building configuration alone, but by the relationships between buildings, parking, yards and lots. These types (Singles, Slots, Rows, Stacks and Courts) are intentionally flexible and do not dictate exact unit counts or layouts, but they are clear enough for both staff and the public to recognize. That clarity allowed us to tailor design standards to each type and incentivize some forms over others where financial feasibility or desired outcomes warranted it.

Unique middle housing types defined for Mountlake Terrace. These types sort common and state-required middle housing types into categories that reflect physical relationships on their sites.

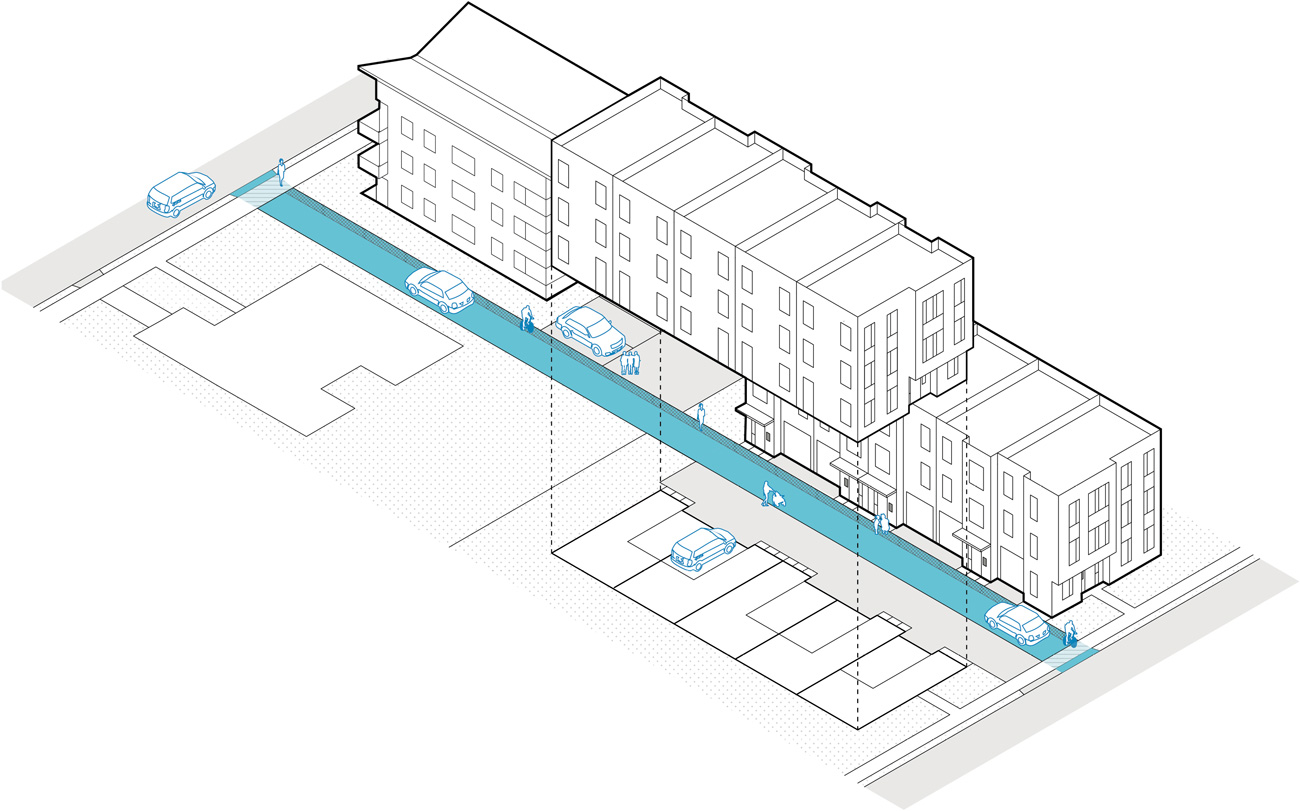

“Slots” are the most instructive example. Across the Puget Sound region, many new townhouse projects place units perpendicular to the street, with narrow façades facing the public realm and larger façades and garage doors oriented to an internal driveway “slot.” Entries are accessed from that shared drive or from narrow sidewalks along a side lot line. First identified and named in Denver, slot homes are often criticized for reduced livability and limited pedestrian engagement. In response, some jurisdictions prohibit them entirely.

But slot homes persist because they are a byproduct of regulatory, legal and market forces, and they remain a feasible way to fit multiple units with attached parking on typical residential lots. Rather than banning them when housing costs and pressures are skyrocketing, we chose to reshape them through design standards that help them contribute to the urban realm.

A central requirement is Building Orientation. Primary façades, including the main entrance, must face an abutting street. When entries are not on the street, they must orient to a common open space, midblock connection or improved parking court. Street-facing façades also cannot read as back-of-house elevations; utilities, waste storage and similar service elements are prohibited on those frontages.

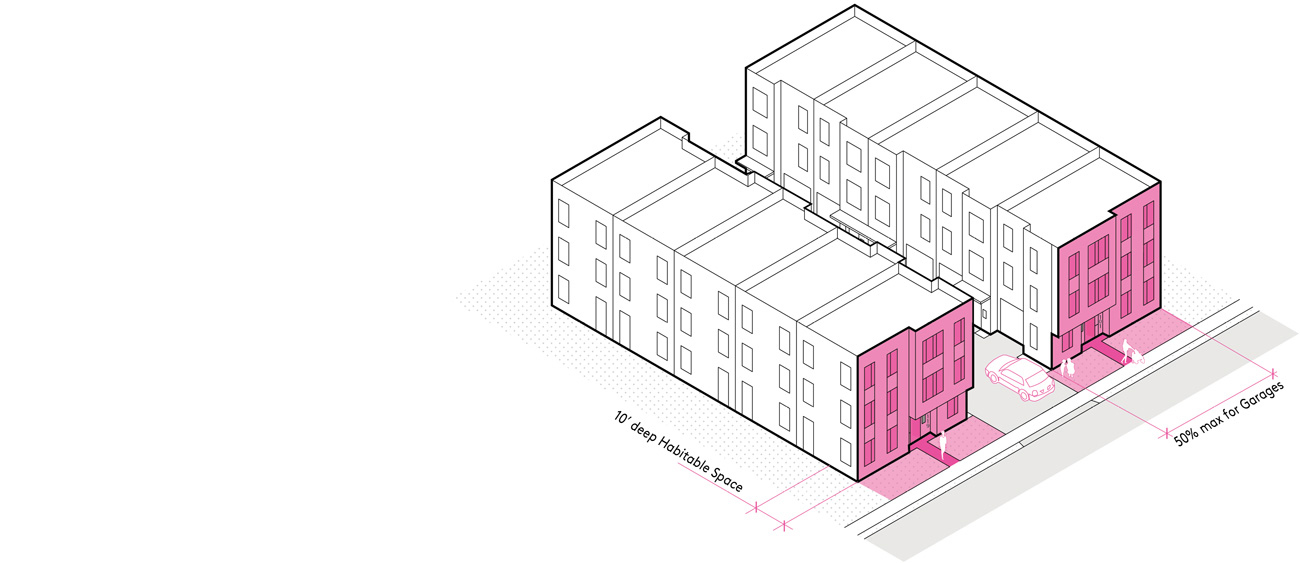

A ”slot” townhome development using Mountlake Terrace’s new Building Orientation and Habitable Space design standards.

Ground-floor use is equally important. To keep garages and driveways from deadening the pedestrian environment, the standards require a percentage of the ground-floor street frontage to be occupied by Habitable Space at least ten feet deep — living rooms, kitchens, foyers, offices — rather than storage or parking.

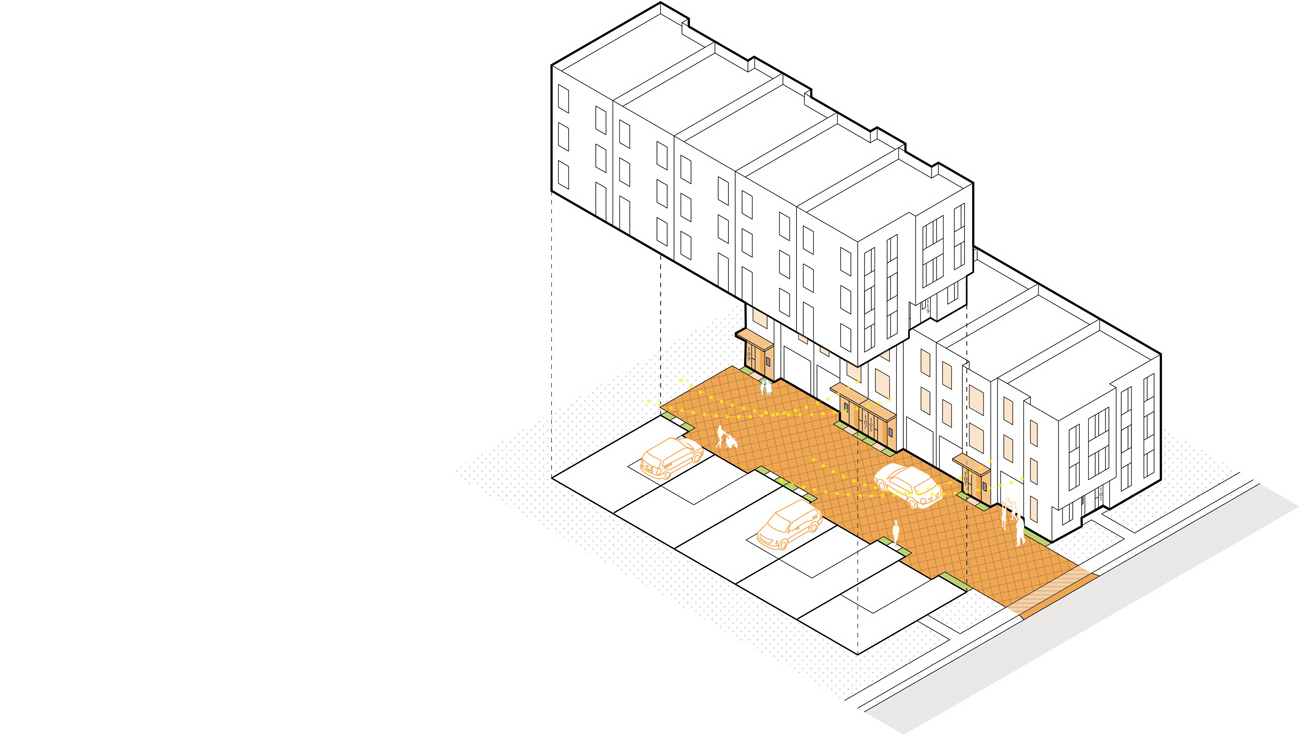

Finally, Improved Parking Courts serve as shared spaces for both vehicles and people. To qualify as true multi-use space, and unlock development bonuses, these courts must include unit entries with address signage, decorative curbless paving, modest landscaping, lighting and transparency on facing façades to support natural surveillance. The intent is to make these spaces function not just for circulation and parking, but for daily activities like neighborly interaction, play and access to homes.

Mountlake Terrace’s new Improved Parking Court design standards, illustrated using a “slot” townhome development.

2. Foster Neighborly Connections

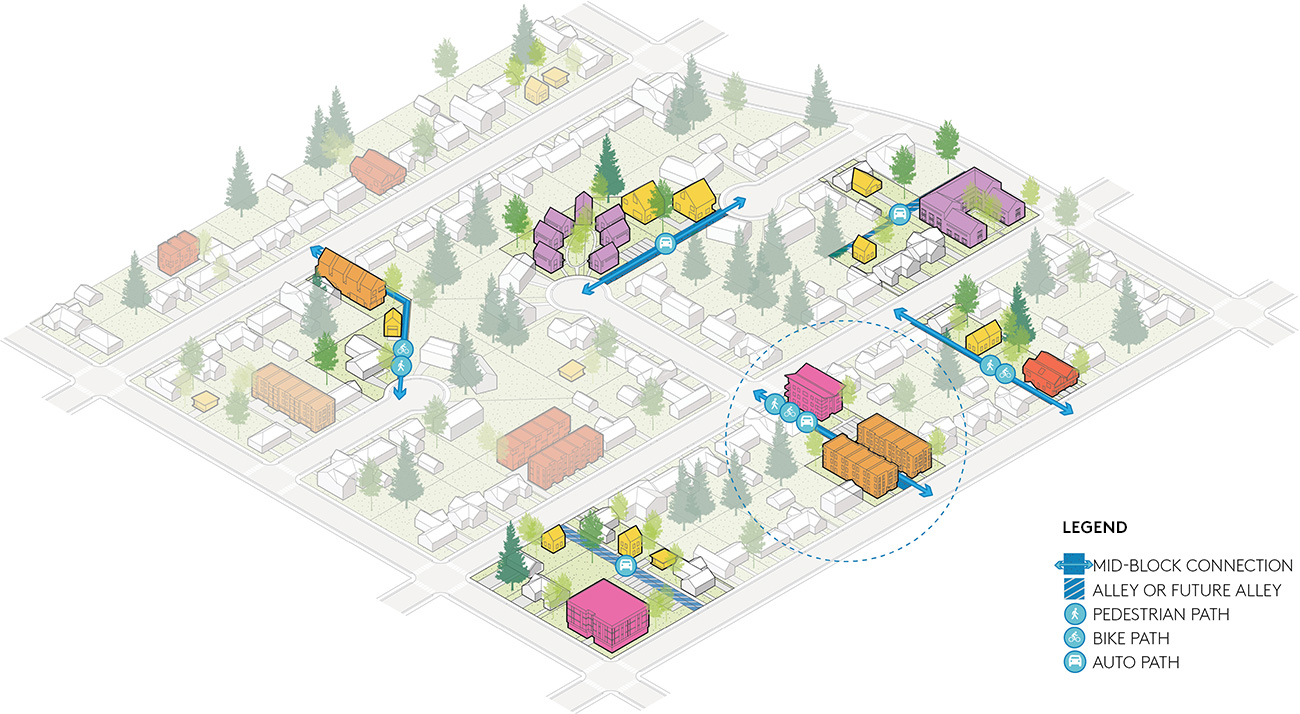

Our work on Mountlake Terrace’s bonusing program shows how designing middle housing together with midblock, and eventually alley, connections can create a finer-grained urban fabric.

Mountlake Terrace was platted in the post–World War II era with a typical suburban pattern. The city core contains walkable rectangular blocks about 300–350 feet long, but most of the city consists of curvilinear streets, cul-de-sacs and loops with very limited through connections. In many areas, blocks stretch up to 1,200 feet — functioning more as barriers than connectors.

Existing neighborhood patterns in Mountlake Terrace.

Although the City aims to support walkable middle-housing neighborhoods, its legacy street grid creates constraints. Long blocks and dead-end streets leave few routes for walking, biking or emergency access, and create limited links to arterials, transit, schools and the town center. The scarcity of corners also limits opportunities for infill and accessory dwelling units. With only two alleys citywide, most blocks rely on driveways and garages facing the street, creating vehicle-oriented frontages and cluttered streetscapes.

Mithun’s code recognizes these limitations and offers a framework for building connectivity over time. To incentivize circulation networks, the code provides area and height “bonuses” that allow additional middle housing units when builders create midblock connections or alley segments benefitting the public.

The same neighborhood in Mountlake Terrace illustrating new midblock and alley connections gained through the new bonusing program.

Midblock Connections are non-motorized access routes located between intersections rather than at corners. They serve pedestrians and bicyclists, with allowance for vehicles or parking. To qualify, they must be placed within the middle two-thirds of any block longer than 300 feet, link a cul-de-sac to another street or cul-de-sac, or extend an existing street through an additional block. Each segment requires a 16-foot recorded easement and signage, with minimal design standards to lower barriers to participation.

Alleys provide rear access that reduces the need for front-facing garages and driveways, and create locations for service functions like trash collection away from the street. To use the alley bonus, builders must locate their portion within the rear eight feet of the lot, contributing to an eventual shared 16-feet-wide alley. Once segments connect to a public street and can support City access and maintenance, the land must be dedicated as public right-of-way. This incremental strategy improves frontage design while assembling a future service and access network.

These connections are not mandatory, but Mountlake Terrace leaders view the code as a pilot for future requirements. Over time, the intent is to stitch together a human-scaled circulation system that supports walking, biking and everyday neighborhood interaction.

A “Slot” townhouse development and neighboring “Stack” sixplex illustrate the ease with which these housing types can accommodate midblock connections via improved driveways and parking courts.

3. Grow Housing and Trees Together

The possibility of losing urban tree canopy under development pressure is a concern as middle housing expands into neighborhoods that historically had more room for trees. Beyond their carbon, stormwater, shading and habitat benefits, trees help define the character of our communities. And in the Pacific Northwest, our emerald landscape is part of our cultural identity. Addressing the housing crisis alongside a changing climate — marked by hotter summers and wetter winters — requires room for both development and tree growth, rather than favoring one at the expense of the other.

Before the “Home In Tacoma” middle housing code project, Tacoma’s city council set a citywide tree canopy goal of 30% coverage by 2030 — ambitious given the existing 17% canopy at the time. Middle housing zones cover about half the city’s land area (25 square miles), and public rights-of-way account for another 20%. These two areas offer the greatest opportunity for canopy expansion. If their combined average canopy reached 32%, Tacoma could meet its 30% citywide goal. During engagement for Home In Tacoma, community members strongly supported adding tree retention and planting requirements in middle housing zones.

In response, Mithun’s landscape architects and planners worked with Tacoma’s urban forestry staff to incorporate tree retention and planting standards into the Urban Residential zones and Urban Forest Manual. To ensure canopy targets were achievable without hindering housing production at middle housing densities, the team test-fitted various configurations of buildings, trees with required soil volumes, utilities, pavement, driveways and stormwater elements.

Existing, removed, retained, and new trees planted on private and in public rights-of-way in a Tacoma middle housing neighborhood, using the new Home In Tacoma tree code.

The resulting requirements range from 20% to 30% canopy coverage depending on zone intensity. Canopy coverage is calculated using credits: new trees earn Tree Credits based on their projected mature canopy as a percentage of lot area, while existing trees earn credit for their actual size. When trees are retained, other development standards may be relaxed to allow flexibility around existing locations. Fees in lieu are allowed down to a minimum “floor” percentage, with funds directed to tree planting in the same watershed.

These layered strategies create a path for Tacoma to grow its housing supply without sacrificing the urban tree canopy that defines its character and climate resilience.

4. Get Into the Gory Details

On small residential lots, every square foot matters. Buildings, yards, trees, parking, utilities and access all compete for limited space. If one element is misjudged, a project can lose units, force essential spaces into unusable dimensions, or raise the cost of remaining homes.

In the final phase of Home In Tacoma, Mithun worked with City technical staff to “site-plan test” six high-intensity middle-housing prototypes selected from thirty initial fits. Using the draft development code, each study evaluated the spatial needs of all elements on typical lots: buildings, setbacks, usable yard space, trees and planting soil, pedestrian and vehicular access, bicycle and car parking, and infrastructure such as water, sewer, power, stormwater systems and solid waste.

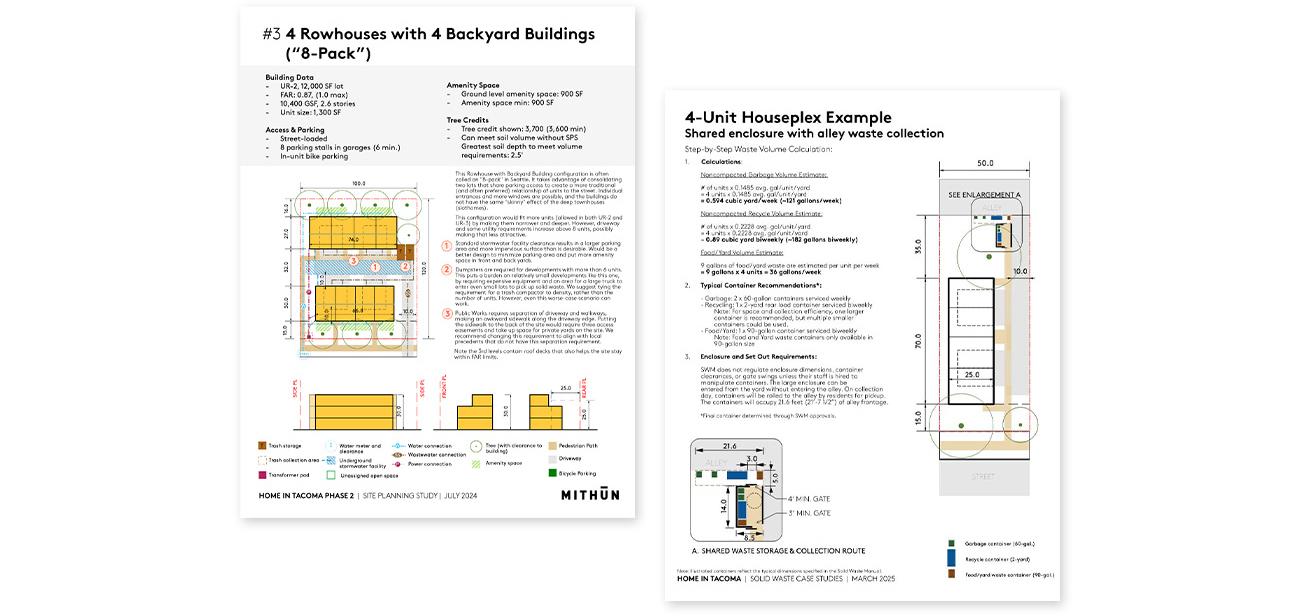

Left: An example Detailed Site Plan Test showing an “8-pack” townhouse development on a prototypical 6,000 square foot lot in Tacoma. Right: A page from Tacoma’s new Solid Waste Management Guide illustrating revised standards for shared containers.

Testing showed that, with some refinements, the intended housing types and densities were generally feasible. Two issues emerged as especially influential: driveway widths and solid waste standards:

Public Works staff reduced driveway widths from 20 feet to 10 feet during Home In Tacoma but still required 16 feet on lots accessed from arterials. Site tests showed that on 50-foot lots, the 16-foot standard combined with setbacks left only half the lot available for housing. Given low traffic volumes and slow speeds on residential drives, and regional precedents allowing eight units to share 10-foot drives, a narrower standard proved more practical.

Tacoma uses automated curbside solid waste pickup, and prior rules did not allow multiple units to share containers. Site tests showed that container dimensions and spacing limited a 50-foot curb frontage to four households, capping density regardless of site capacity. The findings prompted changes to the standard, and Mithun helped develop Tacoma’s first citywide Solid Waste Management Guide to illustrate service options for multifamily and residential sites.

Conclusion

Middle housing is reshaping neighborhoods — and with the right tools, it doesn’t have to come at the expense of livability, climate goals or community character. By pairing smart design standards with neighborhood connectivity options, tree strategies and technical precision, cities can welcome more homes while building more complete, livable, and enduring neighborhoods.